By 1937, giant hydrogen airships were sailing through the world’s skies, ferrying thousands of passengers across oceans and continents. These airships, also called zeppelins, promised quicker transport times than sea ships and offered luxurious accommodations along with spectacular views. The Hindenburg was one such airship, the last passenger aircraft of the world’s first airline. She was the fastest to cross the Atlantic in her day; her passengers enjoyed luxurious accommodations on their transatlantic flight, which included fine dining rooms, music rooms, and comfortable cabins. But in just a few fiery moments, the Hindenburg would be lost. Her destruction would be the end of the era of passenger airship travel.

On May 3, 1937, the Hindenburg departed Frankfurt, Germany for Lakehurst Airfield in New Jersey with 36 passengers and 61 crewmembers. Although not at maximum capacity during her journey to America, the Hindenburg’s return flight was fully booked; many of her passengers were traveling to Europe for the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in London.

The airship flew over Cologne, Germany, and then crossed the Netherlands before following the English Channel out over the Atlantic. The Hindenburg passed over the southern tip of Greenland where she encountered strong headwinds. The original landing, scheduled for 6:00 am on May 6th, was postponed to 6:00 pm because of the delay caused by headwinds and afternoon thunderstorms. To wait for favorable landing weather, the Hindenburg’s captain Max Pruss chartered a course over the skyscrapers of Manhattan, causing a spectacle as people rushed to the streets of the city to catch a glimpse of the airship, then over the seaside of New Jersey. Once notified that the storms had cleared at 6:22 pm, Captain Pruss navigated the Hindenburg back toward Lakehurst for the final approach. Awaiting her arrival was a large crowd of spectators and many news crews, including WLS Chicago reporter, Herbert Morrison, whose eyewitness radio report would become the most famous oral record of the disaster.

The presence of so many reporters and cameras resulted in a well-documented timeline of the disaster:

- 7:00 pm: The Hindenburg makes its final approach to Lakehurst Naval Air Station at an altitude of 650 feet. The landing was to be a high landing, otherwise known as a flying moor because the Hindenburg would drop her landing ropes at high altitude and then be winched down by the ground crew.

- 7:09: The Hindenburg makes a sharp full-speed left to turn to the west because the ground crew is not ready.

- 7:11: Captain Pruss turns the Hindenburg back toward the landing field. All engines idle ahead and the airship begins to slow.

- 7:17: The wind shifts direction from east to southwest, and Captain Pruss orders a second sharp turn starboard.

- 7:18: Captain Pruss orders ballast dropped because the stern was heavy. First 300kg, then 300 more kg, and then 500kg of water ballasts were ordered dropped. The forward gas cells are valved and six men are sent to the bow to trim the airship.

- 7:21 The Hindenburg descends to an altitude of 295 feet and the mooring lines are dropped from the bow. A light rain begins to fall.

- 7:25: The Hindenburg catches fire and quickly becomes engulfed in flames.

On the ground, eyewitnesses ran screaming as passengers and crew jumped from windows. News crews that were assembled caught the ensuing melee as Herbert Morrison of WLS Chicago cried into his microphone, “Oh! The humanity!” Passenger Joseph Späh, a vaudeville comic acrobat, smashed his window with the camera he was using to film the landing, and used his acrobatic skills to roll out the window, injuring only his ankle. The last living survivor, Werner G. Doehner, died November 8, 2019, recalling that his mother pushed him and his brother out the window. They all survived, but his father and sister did not. Survival was a matter of luck; those passengers near the promenade windows on A Deck were able to jump out the windows; those deeper in the airship perished. In total, there were 36 fatalities: 13 passengers, 22 crewmen, and 1 worker on the ground.

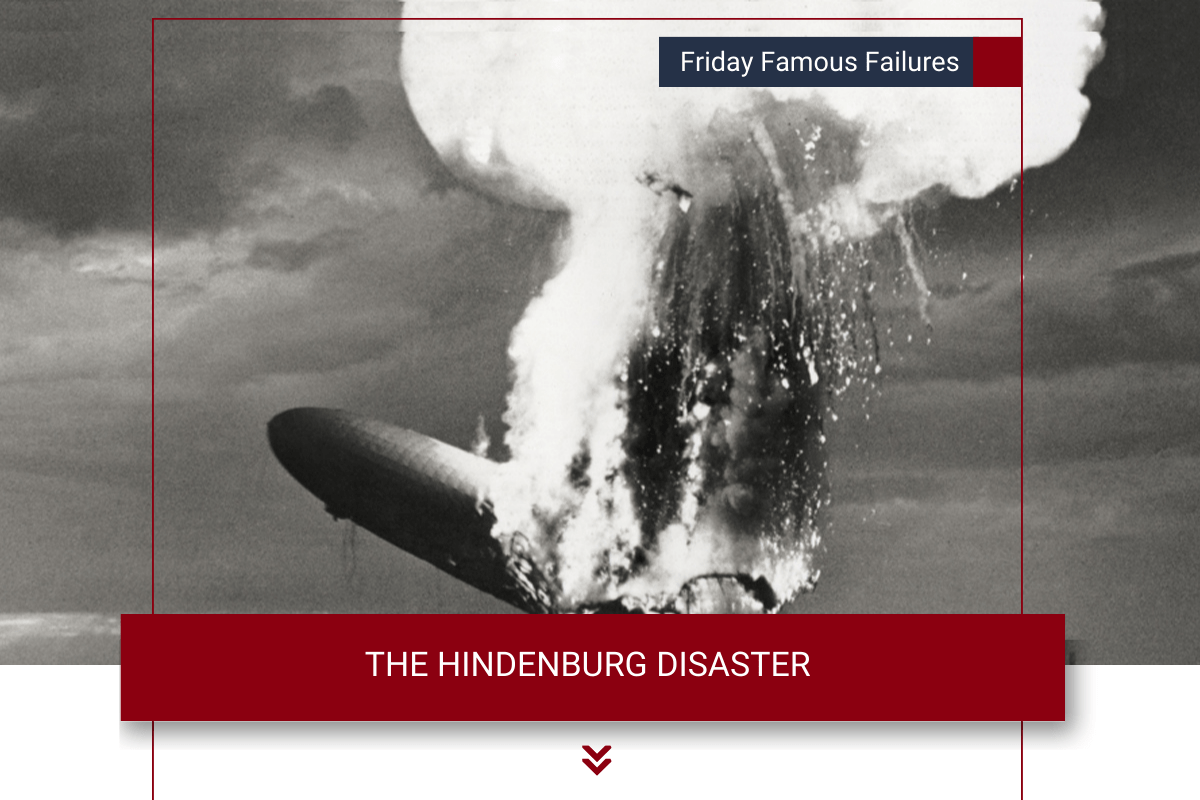

Although investigations were commissioned immediately, the wreckage provided few clues to the cause of the disaster. Complicating the matter further, eyewitness statements of the disaster varied significantly. Commander Rosendahl, Lakehurst Naval Station commander reported seeing a mushroom-shaped flame. Some ground observers saw blue flames, some saw yellow red flames on the port side, and some suggested the fire began just ahead of the horizontal port fin. From the first sign of disaster to the Hindenburg’s bow crashing to the ground, the tragedy was estimated to unfold between 32 and 37 seconds.

Despite these uncertainties, however, several prominent theories emerged concerning what went wrong.

Sabotage

As the Hindenburg was a German-engineered and owned airship, some speculated that someone who hoped to cause problems for the Nazis brought down the Hindenburg. Even surviving passenger Joseph Späh was considered a saboteur at one point. During the trip, the German acrobat would occasionally feed a dog in a freight room—a German Shepard he had brought to surprise his children—and it was thought that he sabotaged the airship during one of these visits. The FBI later investigated this accusation and found no evidence of sabotage.

Electrostatic Discharge Ignited Leaking Hydrogen

After 80 years of research, the most commonly accepted cause of the Hindenburg disaster remains the electric shock theory, which suggests that the difference in electric potential between the ship’s fabric covering (which could hold a charge) and the ship’s framework after it had been grounded by the landing line, caused a spark. Another version of this theory attributes the potential spark to St. Elmo’s fire, a weather phenomenon involving a gap in electrical charge. Whichever may be true, the thought is that a spark ignited an undetected hydrogen leak and started the fire. Today, most researchers share this belief, though the cause of the spark and the source of the leaking hydrogen remain matters of speculation.

Incendiary Paint Hypotheses and Puncture Hypothesis

Two additional theories, the Incendiary Paint Hypothesis and the Puncture Hypothesis, have also been suggested. Retired NASA scientist Addison Bain, who suggested that the compounds in the paint covering the Hindenburg’s canvas skin were the cause of the fire, posed the Incendiary Paint Hypothesis in 1996. The puncture hypothesis suggests that the airship’s structural integrity was stressed over repeated flights and that the final turns made in landing over Lakehurst weakened the structure near the vertical fins, causing a bracing wire to snap and puncture an internal gas cell.

The Hindenburg disaster, which was well-publicized outside of Germany, marked an abrupt end to an era of airship travel. Had the tragedy never occurred, the end of commercial airship travel was likely short-lived regardless. In 1935, just three months before the Hindenburg’s first flight, Pan American Airways’ M-130 China Clipper made its first scheduled flight across the Pacific, ushering in a new, faster form of air travel.

Leave A Comment