On December 7, 1982, engineer Andy Hurdack was recording the installation of a new 1800-foot tower that would serve the airwaves of the surrounding areas of Missouri, Texas. The Senior Road Tower Project, a part of KTXH-TV, operated the tower and several radio stations. The mast was in the final stages of construction. As Andy recorded the raising of the last section of the tower, the supporting bolts suddenly failed, and the entire section fell, cascading a thousand feet to the ground. On the way down, the falling section sheered away guy wires and caused the entire structure to topple. Several riggers fell 1000 feet to their death.

The only sounds on Andy’s tape were his anguished, “Oh, my God!” and several seconds of the roaring collapse. “I heard something snap,” he said later. “Then the tower started falling. I just put my gear down rather hastily and got out of the way.” Because the collapse was caught on camera, the film has provided engineers and scientists the opportunity to closely examine the event. This disaster raised ethical questions about the behind-the-scenes engineering decisions that were made by the parties involved. So, how did these decisions lead to the accident? And what led to this case being one of the most widely debated ethical engineering cases to date?

The antenna was designed and manufactured by Antenna Engineering, Inc., a moderately-sized local firm. A smaller local firm, Riggers, Inc., was contracted to raise and assemble the antenna. During the initial design stages, Antenna Engineering proposed plans to Riggers for their approval, and Riggers approved the plans. These plans contained instructions for the placement of the antenna hoisting lugs, which provided attachment points for the lifting cables that would be used to remove the antenna sections from the delivery truck and to hoist the antenna into the air for the final assembly.

A crew of riggers with years of experience in similar projects was on-site during construction. To help construct the tower, the crew used a vertically-climbing crane mounted on the already-constructed portion of the tower to lift each new section. To complete the construction, the crew would then use this crane to help mount the two-section antenna onto the top of the tower. The design called for a three-legged tower, and as each new section was lifted, it was positioned and bolted onto the previous tower sections. The tower legs were 8-inch diameter solid steel bars; each tower section weighed approximately 10,000 pounds.

When the final antenna sections arrived, the project had gone off without incident; however, the last section of the antenna was different because it had microwave baskets attached to its sides. While the placement of the hoisting lugs allowed the antenna to be lifted horizontally off the delivery truck, the baskets interfered with the lifting cables when the antenna was rotated to a vertical position.

A few weeks before the incident, Riggers approached Antenna Engineering and asked if it was possible to remove the microwave baskets on the top 100-foot section of the tower so they could lift the antenna into position. Once lifted into position, Riggers proposed to reinstall the baskets after the section was in place. Antenna Engineering responded that removing the baskets would void the warranty.

While Riggers had seen and approved the initial plans drawn up by Antenna Engineering, they did not have the same technical expertise as the engineers at Antenna Engineering. While they were skilled tradespeople, the employees of Riggers were not Professional Engineers.

Riggers then requested the help of the chief engineer at Antenna Engineering to review their plans on lifting the antenna without removing the microwave baskets. The engineer at Antenna Engineering refused to approve, or even review, the design. Instead, after consulting with the firm, the engineer decided that by saying anything to Riggers, Antenna Engineering would assume liability in the case of an accident. Antenna Engineering essentially stated that their job was to design and build the antenna, and Riggers was responsible for assembly.

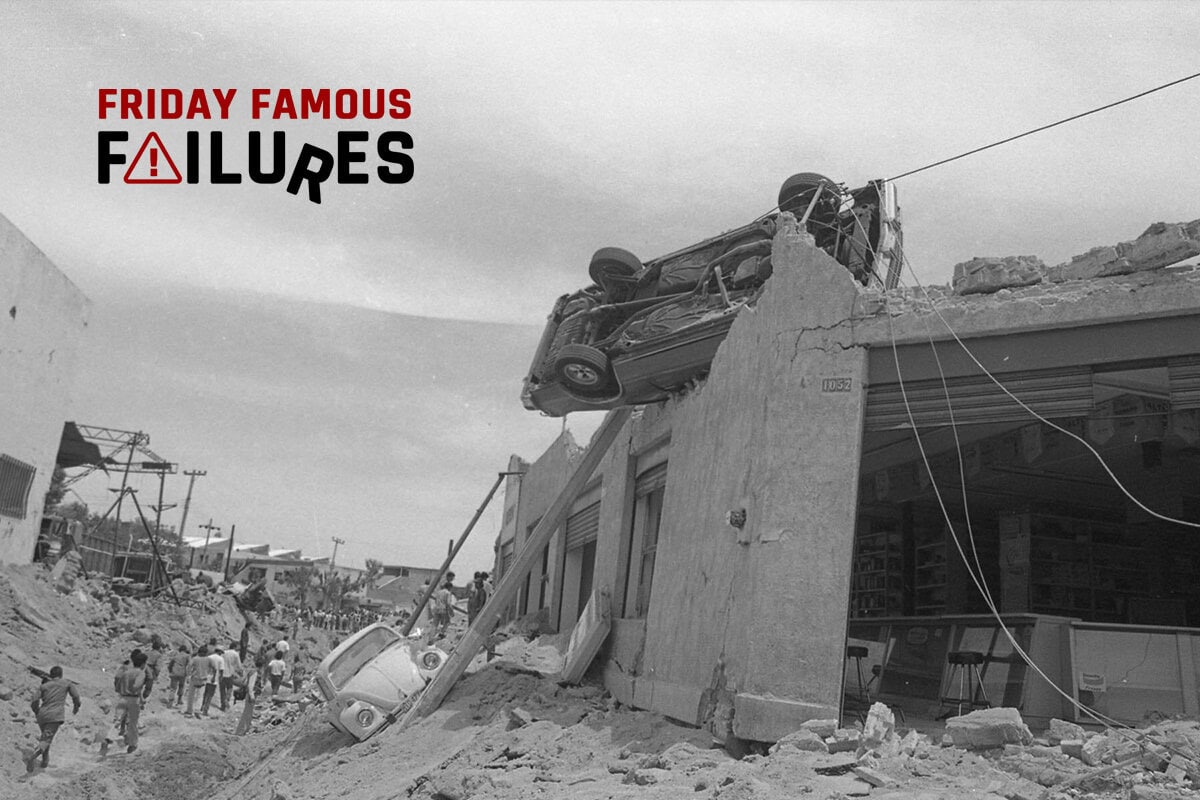

Without Antenna’s consult, Riggers proceeded with their plan. They attached a long channel to the antenna section with several U-bolts. In this plan, Riggers hoped that by attaching the lifting cables to the end of the added steel section, the antenna section could be raised vertically without obstruction from the microwave baskets. They used bolts that they believed were of the proper strength, but they did not realize that the piece of steel they attached also added a large weight, which was spread through the U-bolts. In the end, seven people died as a result of this tragic and inadequate design flaw.

Findings From The Investigation

After the incident, an investigation found that when designing the makeshift lug extension, the rigging crew underestimated the load on the lugs by a factor of seven. This engineering mistake compounded the risk created by proceeding with the assembly of the last tower section even though the presence of microwave receivers made the intended assembly procedure impossible.

In addition to these mistakes, the investigation found malfeasance: the u-bolts used by the rigging crew for the lug extensions, which were the actual point of failure in the accident, were rated by their manufacturer for twice the load they could actually withstand.

The investigation highlighted the following ethically-irresponsible decisions associated with this tragedy: lack of responsible engineering in jury-rigging the lug extensions without proper engineering review, the miscalculation of the mechanical load of the assembly method, and the u-bolt manufacturer’s misrepresentation of the u-bolt rating. An argument could be made that Antenna Engineering has some culpability here, too. This disaster would not likely have happened if Antenna Engineering had accounted for constructability considerations in their original design.

Antenna Engineering should have required Riggers to have a 3rd party Professional Engineer design the modification and submit the procedure for review to Antenna.

Monday quarterback aside, the Rigger Company should have retained a structural PE to design the lifting system and components. They were worried, but not worried enough to consult with a professional.

On the other hand, because of their stringent requirement to lift the antenna section with the microwave baskets attached, the Antenna Engineering Company should have been available to review the Riggers plans, I believe they have some responsibility on the catastrophe and of course, the u-bolt manufacturer share responsibility for misrepresenting the u-bolts rating.

I believe that attaching the microwave baskets created additional bending moments that could not be resisted by the bolts’ strength.

Without seeing contracts, the riggers were responsible for means and methods and were not prevented from hiring an engineer to check their rigging approach. Temporary construction is often a part of construction that has little or nothing to do with the final finished product. They could have used a helicopter for instance, a means not regulated by the manufacturer whose responsibility was to the structural integrity after the antenna was erected. The riggers had every opportunity to weigh in on the constructability of the antenna during the design thereof, were experienced, approved them in principle. Just because the antenna engineers are engineers and probably capable of doing the constructability analysis does not make it their responsibility any more than a chiller manufacturer’s engineer for their product makes them responsible for the installation of the chiller after it leaves the factory.

The engineering design should have included stability of both the static, finally-assembled structure and every step of the erection. If the engineers required that the antennas not be disturbed in the final piece then they were responsible for designing the change in erection procedures. Why they disavowed that responsibility rather than insisting on it is beyond me.

Forgive me but I must note that this story is just about totally incorrect save the collapse of the tower. Senior Road tower group was a consortium of 9 FM stations serving the Houston area and had no connection to a television station. The tower itself was designed and manufactured by Stainless Inc, the antenna (a 12 bay “cavity backed radiator”) designed by Harris Corporation aka Gates Radio had no such appurtenances you describe. The erector of the tower was World Wide Tower (Dan Weberneck). The antenna was also “picked” by Worldwide utilizing ginpole which was secured and cantilevered to the top sections of the tower after being “jumped” there. At the time of concept, specification, design and construction of the project I was the VP of engineering of the corporation (LIN) that owned one of the FM stations KILT-FM. While your description of the failure may be somewhat valid I recall the ultimate cause of the failure was a shackle connected to the load line and antenna. It was an incredible loss of life for a wonderful bunch of riggers who I knew personally and the ultimate demise of Worldwide. I must point out that as an electrical RF engineer I only wrote the purchase specification for the electrical characteristics of the antenna and not its structural ones

Antenna should have warned Riggers that they needed a qualified professional engineer to review the plan and design the system to safely handle the loading and stresses on the bolts. They had an obligation to the public once they were aware of the risks.

The event is vivid and current in my mind despite being 38 years ago and evokes an emotional response even today. So tragic, and so easily avoidable. I believe my responsibility does not end when I do my part right. In my projects I am always thinking of how something can be built or serviced, how others might mess up, and how my design can mitigate or avoid mistakes by others. For the good of the project, I regularly scan other parts of the project for things that “don’t look right”. To do less is irresponsible.

I would think that if you design equipment that cannot actually be installed, that your responsibility should include selling a structure that must have engineering instructions on how to install. This would seem to create 50% liability to the Antenna Engineering Firm.

The safety climate was quite different in the 1980’s compared to today. Everyone was too trusting.

Now-a-days a safety shut down would have been called and work would have been stopped until a revised lift plan developed.

The engineering company did not deliver a package that could be assembled as designed.

When this was discovered the owner should have stopped work and demanded a viable assembly method be developed. The riggers could not have known the center of gravity of the assembly was not compatible with the lift plan they were given until they actually rigged it. Their mistake was failing to refuse to work until a viable rigging scheme was submitted.

I would concur with the culpability of Antenna Eng’g since they did not consider the microwave baskets in the constructability review it did with Riggers. Further, when the issue was brought to the attention of Antenna Eng’g’s chief Engineer, he had a responsibility to stand with Riggers to identify a safe solution.

I believe that Antenna Engineers should have reviewed the erection procedure.

It is impossible to make anything foolproof because fools are so ingenious. Antenna refused to modify the design, so the Riggers should have had the insight to do the obvious – hire an engineer to make the assembly work, then charge Antenna for non-performance. Since engineers are usually not adept at communication, it would be a good thing for the State Boards to provide a compendium of what if’s e.g.:

What if the design does not work?

A contact the engineer of record, if the engineer is not responsive

B hire an engineer to correct the design and bill the original engineer for the job

What if the proposed event does not look safe

A. see previous

What if ….

In my work as a Commissioning Engineer I often have to make a decision of correcting a design error in the field or pushing to have the design firm correct the error and resubmit construction drawings. I generally argue that if the design firm makes the correction, the correction goes through the design firm’s QA/QC process and then it comes back to me for review and implementation. If I correct the design error in the field, I take on the design, QA/QC, review, and implementation roles all at once. This example is a good reinforcement to push to have design errors corrected by the design firm and vetted through the entire process to avoid unilateral field changes that could lead to unintended consequences.

Thanks for sharing the experience. jak

The antenna section should have been designed for proper rigging possibly removing the the microwave baskets to reduce load and facilitate the lift. The tower engineer should have approved the rigging designed or required that the riggers had the design reviewed and approved by a PE.

Antenna Engineering had a responsibility to see the project through to completion. Riggers had a responsibility to procure an appropriately skilled engineer for the redesign. The bolts would have failed regardless, so no liability should go there, although an audit of their products should ensue.

I think one point has been overlooked. Dollars! I think everyone agrees that any change to a complicated operation such as tower erection should have been professionally reviewed. The cost of this review would have to come out of the pocket of one of the parties. Each thought an other should pay, with good reasoning to them.

The courts get involved after the loss of life, material, and large dollars.

How can conditions like this be reversed so the right decisions get made, and reviews get made, and paid for before unfortunate incidents and loss of life. There are no winners in situations like this.