This is the November 2022 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think? This series is comprised of case studies from NSPE archives, involving both real and hypothetical matters submitted by engineers, public officials and members of the public.

Your peers and the NSPE Board of Ethical Review have reviewed the facts of the case as shown below. And, here are the results.

Your opinion has been registered for the November 2022 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on November 22.

Your opinion has been registered for the November 2022 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on November 22.

A Review of the Facts

Engineer Troy serves as a director of a building department in a major city. Troy has been concerned that the city has been unable to provide a sufficient number of qualified individuals to perform adequate and timely building inspections as a result of a series of budget cutbacks and more rigid code enforcement requirements. Each code official member of Troy’s staff is often required to make as many as 60 code inspections per day. Troy believes that there is no way even the most conscientious code official can make 60 adequate, much less thorough, inspections in one day, particularly under the newer, more rigid code requirements for the city. These new code requirements greatly enhance and protect the public’s health and safety. The code officials are caught between the responsibility to be thorough in their inspections and the city’s desire to hold down costs and generate revenue from inspection fees. Troy is required to sign off on all final inspection reports.

Troy meets with the chairman of the local city council to discuss his concerns. The chairman indicates that he is quite sympathetic to Troy’s concerns and would be willing to issue an order to permit the hiring of additional code officials for the building department. At the same time, the chairman notes that the city is seeking to encourage more businesses to relocate into the city in order to provide more jobs and a strengthened tax base. In this connection, the chairman seeks Troy’s concurrence on a city ordinance that would permit certain specified buildings under construction to be “grandfathered” under the older existing enforcement requirements and not the newer, more rigid requirements now in effect. Troy agrees to concur with the chairman’s proposal, and the chairman issues the order to permit the hiring of additional code officials for the building department, which Troy believes the city desperately needs.

Was it ethical for Troy to agree to concur with the chairman’s proposal under the facts?

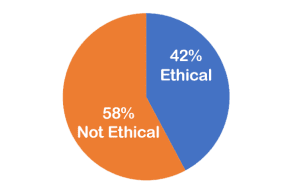

Here is the result of our survey of your peers:

Applicable NSPE Code References:

Code I.1

Engineers, in the fulfillment of their professional duties, shall hold paramount the safety, health and welfare of the public.

Code II.1.b

Engineers shall approve only those engineering documents which are in conformity with applicable standards.

Code II.3.b

Engineers may express publicly technical opinions that are founded upon knowledge of the facts and competence in the subject matter.

Code III.1.b

Engineers shall advise their clients or employers when they believe a project will not be successful.

Discussion

The duty to hold paramount the public health, safety, and welfare is among the most basic and fundamental obligations to which an engineer is required to adhere. While in many instances, the obligation is often clear and obvious, in other instances, there could be an obligation on the part of the engineer to balance competing or concurrent obligations or responsibilities to protect the public health and safety. The facts of this case are in many ways a classic ethical dilemma faced by many engineers in their professional lives. Engineers have a fundamental obligation to hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public in the performance of their professional duties (See Code I.1). Moreover, the Code provides guidance to engineers who are confronted with circumstances where their professional reputations are at stake. Sometimes engineers are asked by employers or clients to sign off on documents about which they may have reservations or concerns (See Code II.1.b.).

The Board has addressed public health and safety issues in the code and approval process on numerous occasions. In BER Case 92-4, Engineer A, an environmental engineer employed by the state environmental protection division, was ordered to draw up a construction permit for the construction of a power plant at a manufacturing facility. He was told by a superior to move expeditiously on the permit and “avoid any hang-ups” with respect to technical issues. Engineer A believed the plans as drafted were inadequate to meet the regulation requirements and that outside scrubbers to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions were necessary, and without them, the issuance of the permit would violate certain air pollution standards as mandated under the 1990 Clean Air Act. His superior believed that the plans, which involved limestone mixed with coal in a fluidized boiler process that would remove 90% of the sulfur dioxide, would meet the regulatory requirements. Engineer A contacted the state engineering licensure board and was informed, based upon the limited information provided to the Board, that suspension or revocation of his engineering license was a possibility if he prepared a permit that violated environmental regulations. Engineer A refused to issue the permit and submitted his findings to his superior. The department authorized the issuance of the permit.

The Board concluded that (a) it would not have been ethical for Engineer A to withdraw from further work in this case, (b) it would not have been ethical for Engineer A to issue the permit, and (c) it would be ethical for Engineer A to refuse to issue the permit. Specifically, the Board determined that it would not have been ethical for Engineer A to withdraw from further work on the project because Engineer A had an obligation to stand by his position consistent with his obligation to protect the public, health, safety, and welfare and refuse to issue the permit. Said the Board, “Engineers have an essential role as technically-qualified professionals to ‘stick to their guns’ and represent the public interest under the circumstances where they believe the public health and safety is at stake.”

As early as BER Case 65-12, the Board dealt with a situation in which a group of engineers believed that a product was unsafe. The Board then determined that as long as the engineers held to that view, they were ethically justified in refusing to participate in the processing or production of the product in question. The Board recognized that such action by the engineers would likely lead to loss of employment.

Turning to the facts of the present case, Troy is faced with a predicament with a variety of options and alternatives. First, Troy could interpret the situation presented as one involving “trade-offs,” in which Troy must weigh one “public good” (a better building inspection process) against a competing or concurrent “public good” (a consistent code enforcement process). In such a situation, Troy could arguably rationalize a decision to permit the inconsistent application of a building code in order to accomplish the larger objective of obtaining the necessary resources to hire a sufficient number of code enforcement officials to provide proper protection to the public health and safety. On the other hand, Troy’s decision to permit developers to avoid compliance with the newer, updated building code enforcement requirements might potentially cause a real danger to the public health and safety if a new facility causes harm to the public because of its failure to comply with the more updated code requirements. In addition, agreeing to the chairman’s arrangement has the appearance of compromising the public health and safety for political gain.

While this case presents a difficult dilemma for Troy, on balance, the Board believes that previous BER cases provide sufficient guidance for Troy. Each of the earlier cases discussed present a constant theme that the engineer must hold the public health and safety paramount and that the engineer has a responsibility to insist, however strongly and vociferously, that public officials and decision-makers take steps and corrective steps if necessary to see that this obligation is fulfilled. The Code of Ethics makes it clear that engineers have an obligation to advise their clients or employers when they believe a project will not be successful. In this case, Troy should make it plain and clear to the chairman that “righting a wrong with another wrong” does grave damage to the public health and safety (See Code III.1.b.). Troy should insist that the public will be seriously damaged in either case and that if the integrity of the building code enforcement process is undermined for short-term gain, the city, its citizens, and its businesses will be harmed in the long term.

The Ethical Review Board’s Conclusion

It was not ethical for Troy to agree to concur with the chairman’s proposal under the facts. Additionally, it was not ethical for Troy to sign inadequate inspection reports. (See Section II.1.b.).

BOARD OF ETHICAL REVIEW

Lorry T. Bannes, P.E., James G. Fuller, P.E., Donald L. Hiatte, P.E., Joe Paul Jones, P.E., Paul E. Pritzker, P.E., Richard Simberg, P.E., C. Allen Wortley, P.E., Chairman

Note – In regard to the question of application of the Code to corporations vis-a-vis real persons, business form or type should not negate nor influence conformance of individuals to the Code. The Code deals with professional services, which services must be performed by real persons. Real persons in turn establish and implement policies within business structures. The Code is clearly written to apply to the Engineer and it is incumbent on a member of NSPE to endeavor to live up to its provisions. This applies to all pertinent sections of the Code. This opinion is based on data submitted to the Board of Ethical Review and does not necessarily represent all of the pertinent facts when applied to a specific case. This opinion is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as expressing any opinion on the ethics of specific individuals. This opinion may be reprinted without further permission, provided that this statement is included before or after the text of the case.

Perhaps clarify if the original buildings currently under construction were permitted under the “old” code, or, were permitted under the “new” more stringent code.

Absent a specific change that materially affected public safety, allowing buildings to be finished under the “old code” doesn’t seem inappropriate. If this allowed them to cut corners that were safety related, it would be unethical to go along with it.

Interesting. I find that most buildings that are already under construction (as indicated in the description) are normally allowed to retain following the code at the time construction started. I could see real issues if you designed a building to one set of codes and they were changes midway through the construction. So that part did not seem unethical to me but instead normal. Do others normally see project having to incorporate new codes as they are built?

I thought the buildings under construction had already gone through the code review under the earlier code and found to be in compliance before the building permits were issued.

‘Politics’ rears its ugly head. Ethically, inspections must be done using the codes and requirements in effect AT THE TIME OF THE INSPECTION. Ergo, it is unethical to allow buildings under construction to be evaluated under older, less rigorous requirements.

If a structure is designed and permitted under an existing code, I don’t believe it is ethical to require the structure to be redesigned because of a code change after the fact.

One key question that is not answered is whether the newer standards are correcting a significant safety deficiency that the old codes allowed. Generally, the codes in effect at the time the permits were issued should control, but if the old codes have significant safety issues, then codes in effect at the time of inspection should prevail. So the question becomes, what is “significant”?

This is what I was thinking as well. The part that seemed unethical to me, was only allowing SPECIFIC buildings currently under construction to be grandfathered in (and not ALL buildings currently under construction).

Insufficient facts were presented for an informed opinion in this case. That informed decision would be based, in part, on the specific public safety issues involved for both the safety inspections and the evolving code requirements. That has only been discussed in generalities. In my opinion, specifics matter.

Troy should have been a “no vote” as he definitely has conflict of interest. The politics and rules adoptions are done by lawmakers not inspectors, let each do their job.

It is standard practice to allow buildings under construction with a valid building permit to continue under the code at the time the permit was issued, with the assumption that the old code provided adequate safety. If there is no specific safety issue under the new code that the old code didn’t address, then I think the engineer was acting ethically in his decision with the council chairman, but there was no specific information otherwise to indicate the engineer acted unethically.

We need some clarity. Unethical implies that the old code was woefully deficient in protecting the public. In any case if the inspectors are doing 60 inspections per day it is doubtful that this protects the public in any way whether the inspection is based on the old or the new code.

I too disagree with the board’s conclusion that it was unethical, being that the “under construction” was permitted under the code of that time.

Not enough information has been given to make a determination. More needs to be known about the specific codes and their effect on the public. Without more information I don’t feel that I can judge.

Agree, insufficient information as to what the deficiencies were in the old code. Also, “Grandfathering” is fairly common and probably more legally defensible than changing code requirements on a building under way, unless there are glaring safety deficiencies in the older code. Otherwise, a mid stream change in requirements could be considered as being equivalent to an “ex post facto” law, in other words equivalent to using a law to find someone guilty of violation of a law that did not exist at the time of the occurrence, which is prohibited by the US Constitution. In other words, say I was injured as a child due to not being restrained in a car accident in the 1950’s my parents could not be found guilty of such because the law requiring such did not exist until 20+ years later.

To finish: Therefore I would regard this to be an ethical action.

Far too often code changes are enacted to benefit an interested party or limit competition. That evaluation should have been part of Troy’s determination of whether the grandfathering affected the safety, health and welfare of the public. I agree with the board that it was not ethical for Troy to sign inadequate inspection reports, but that wasn’t the question asked. All engineering involves trade-offs, and factors of safety that are less than infinite. Give the guy a break!

The problem with allowing buildings that are already UNDER CONSTRUCTION to be grandfathered to conform to previous, less stringent code requirements should be obvious. It is true that some jurisdictions do allow for modified and less stringent requirements for work on existing buildings — the Rehabilitation Subcode in New Jersey is a perfect example. BUT… the construction official can’t ethically allow the design to be modified DURING CONSTRUCTION — which is what the narrative here says: “…a city ordinance that would permit certain specified buildings under construction to be ‘grandfathered’ under the older existing enforcement requirements…” — without the concurrence of the engineer/architect of record. They signed/sealed documents based on specific standards, and neither the code official nor the city council can simply relax those standards and change the standard of construction mid-stream absent the approval of the design professional. Codes are generally made more stringent because they’ve been found to be insufficient to adequately protect public safety. If I’m the design professional, and someone else changes the standard of construction, I’m immediately revoking my endorsement of the plans.

I agree there was insufficient information provided to determine whether the buildings under construction should have been allowed to continue under the old code. We don’t know anything about the dates of application, permitting, beginning construction, or the dates of the code changes, or the subject of the code changes relative to the specific buildings. in most cases code changes are not effective until adopted by the state or local authorities, so the politicians do and should have input as to the timing of implementation of code changes, barring some dire defect in the old code.

I had considered this unethical. I think the engineer and councilman could have handled this in a way that was ethical. As mentioned in the comments, the old code was apparently good enough at one time in history. The City could have issued a blanket change to allow projects under construction to follow the old code. Instead the councilman “arm-twisted” the engineer to allow specific projects to follow the old code in exchange for approving additional staff. This was the essence of the unethical behavior by both the councilman for suggesting, and the engineer agreeing.

Interesting discussion. As others have indicated, these buildings are currently permitted and under construction and designed to the existing codes. Enforcing new codes after the fact may invalidate the design parameters and force significant additional costs to the projects. The new codes haven’t been provided…”older existing enforcement requirements and not the newer, more rigid requirements now in effect.”…What are those changes? Structural? if that, kiss the project goodbye. Electrical, Plumbing, Energy Efficiency (typically not an issue to public safety) and will add to project costs potentially enough to cancel the project.

What was unethical was the quid pro quo in the politics game for hiring new inspectors to meet public safety needs as stated by Pat above.