This is the May 2024 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think? This series is comprised of case studies from NSPE archives, involving both real and hypothetical matters submitted by engineers, public officials, and members of the public.

Your peers and the NSPE Board of Ethical Review have reviewed the facts of the case as shown below. And, here are the results.

Your opinion has been registered for the May 2024 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on

May 28.

Your opinion has been registered for the May 2024 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on

May 28.

A Review of the Facts

Engineer Jack is the principal of a small-sized consulting engineering firm. Approximately 50 percent of the work performed by Jack’s firm is performed for the county in which the firm is located. The value of the work for the firm is estimated to be approximately $150,000 per year.

Jack is requested to make a $5,000 political contribution, the maximum amount allowed by law, to help pay the cost of the media campaign of the county board chairman. After subsequent thought, Jack makes a $2,000 contribution to the campaign of the chairman, a person Jack has known for many years through mutual public service activities as well as their activities on behalf of the same political party. The county board chairman serves in a part-time capacity and receives $9,000 per year for his services. Other members of the board receive $8,000 per year for their services.

As required under the laws of his state, Jack reports the campaign contributions to the state board of elections and correctly certifies that the contributions do not exceed the limits set by the law of the state. These contributions and the contributions of other firms in the county are reported by members of the local media who appear to suggest that Jack and other firms have contributed to the campaign in anticipation of receiving work from the county. Jack continues to perform work for the county after making political contributions.

What Do You Think?

Is it unethical for Jack to continue to perform work for the county after making the $2,000 contribution to the campaign of the county board chairman?

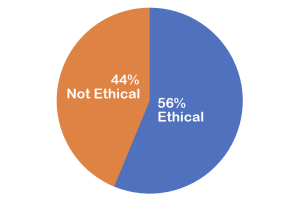

Here is the result of our survey of your peers:

Applicable NSPE Code References:

II.3.a

“Engineers shall be objective and truthful in professional reports, statements, or testimony. They shall include all relevant and pertinent information in such reports, statements, or testimony, which should bear the date indicating when it was current.”II.5.b

“Engineers shall not offer, give, solicit, or receive, either directly or indirectly, any contribution to influence the award of a contract by public authority, or which may be reasonably construed by the public as having the effect or intent of influencing the awarding of a contract. They shall not offer any gift or other valuable consideration in order to secure work. They shall not pay a commission, percentage, or brokerage fee in order to secure work, except to a bona fide employee or bona fide established commercial or marketing agencies retained by them.”III.1.e

“Engineers shall not promote their own interest at the expense of the dignity and integrity of the profession.”

Discussion

For many years, the engineering profession has been grappling with the ethical issues involved with political contributions by individuals to state and local candidates.

Over the years, the Board of Ethical Review has had to examine the question of political contributions. Case 62-12, the first case of its kind, involved engineers who were officers or partners of various organizations such as consulting firms, construction companies, or manufacturing companies who made it a practice to contribute to campaign funds on behalf of those seeking public office. The engineers also contributed as individuals to both major political parties and in some cases to rival candidates for the same office.

The Board ruled that it was not unethical for an engineer to contribute to a political party or a candidate per se, but it is unethical to make contributions in the expectation of being awarded contracts based on favoritism. The Board began its discussion by noting: “Here we must deal with motivation-what was in the mind of the contributor. It is beyond doubt that the engineer as a responsible citizen has and should have the same opportunity as others to hold political views and support the party or candidate of his choice for political office. Such interest and activity is to be encouraged.”

The Board noted however: “The implication of the facts, however, is that the political contributions were made to curry favor and place the engineer, and through him his firm, in a favorable position to secure contracts through the influence of the candidate elected to a public office which determines the award of such contracts.”

In concluding its discussion, the Board noted: “It is hardly possible to draw a precise line in dollar amounts for the purpose of defining when a political contribution becomes an improper incentive to secure contracts on the basis of favoritism. As in all ethical applications, the only sound rule is that when conduct may raise suspicion and doubt as to motive, it is the better part of wisdom to stay well within the line.”

Thereafter, in Case 73-6, Engineers A, B, and C made political contributions in the sums of $150, $1,000, and $5,000, respectively, to a candidate for governor of the state in which the firms they are associated with as principals are located. The candidate they supported was victorious. Subsequently, the firms in which A, B, and C are principals, received several state contracts for engineering services with total fees ranging from $75,000 to $4 million over a two-year period.

With two members dissenting, the Board found that in the absence of a showing of improper intent, Engineers A, B, and C were not acting unethically at the time they made their contributions, that Engineer A was not unethical for taking state contracts under the circumstances since the contribution was in a nominal amount, but that Engineers B and C were unethical for taking state contracts under the circumstances since their contributions were each over a nominal amount. The dissenting position criticized the majority conclusion that Engineers B and C were unethical noting: “As long as the present system of financing political campaigns is in effect, and in light of the conclusions reached in this case, any engineer who relies on governmental or public works type of engagements for a substantial portion of his practice would have to refrain from acting meaningfully and constructively in the political process. With candidates dependent on donations and contributions for financing campaigns, it is naive to assume that any elected legislator is going to heed the advice or requests for support of legislation and administration by persons who have not given him strong support for his campaign efforts including the financing of such efforts.”

What we are faced with here is a fundamental clash between deeply-rooted ethical principles and a profession faced by the pressures of the business environment. The language in the Code is clear; this Board has interpreted the language on more than two occasions and has been fairly consistent in its BER interpretation. Nevertheless, we continue to hear the refrain from many within the profession that “engineers are pressured into making contributions,” and “it’s a matter of survival.” We must respond, however, that fundamental ethical principles stated in unequivocal terms cannot be bent or broken for economic expediency or gain.

Under the facts of this case, the requested political contribution of $5,000 was not a nominal contribution for the office of chairman of the county board and therefore was in violation of the Code of Ethics. Nominal political contributions should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis depending upon the nature of the political office involved, the size of the jurisdiction that the public official serves, and other appropriate considerations based upon the unique nature of the office. But with most provisions of the Code, the greatest responsibility falls upon the shoulders of individual engineers who must make a decision based upon their own consciences as to what is appropriate. In this particular case, it is our judgment that a political contribution of $2,000 represents the upper limit of a nominal contribution and therefore is not in violation of the Code.

The Ethical Review Board’s Conclusion

It would not be unethical for Jack to perform work for the county after making a nominal political contribution of $2,000 to the reelection campaign of the county board chairman.

BOARD OF ETHICAL REVIEW

Eugene N. Bechamps, P.E.; Robert J. Haefeli, P.E.; Robert W. Jarvis, P.E.; Lindley Manning, P.E.; Paul E. Pritzker, P.E.; Harrison Streeter, P.E.; Herbert G. Koogle, P.E.-L.S., chairman

Note – In regard to the question of application of the Code to corporations vis-a-vis real persons, business form or type should not negate nor influence conformance of individuals to the Code. The Code deals with professional services, which services must be performed by real persons. Real persons in turn establish and implement policies within business structures. The Code is clearly written to apply to the Engineer and it is incumbent on a member of NSPE to endeavor to live up to its provisions. This applies to all pertinent sections of the Code. This opinion is based on data submitted to the Board of Ethical Review and does not necessarily represent all of the pertinent facts when applied to a specific case. This opinion is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as expressing any opinion on the ethics of specific individuals. This opinion may be reprinted without further permission, provided that this statement is included before or after the text of the case.

So, Jack’s $2,000 contribution is ethical, but a $2,001 contribution would not be?

Would a larger contribution be allowed if Jack and the County Board Chairman were friends? Close friends? How close is close enough?

Trying to discern, rate and rank the motivations for political contributions and most other voluntary actions is a fool’s errand. It’s difficult for most of us to fairly assess ourselves, much less others. The more complex the situation, the fuzzier the discernment.

Aiming to be politically-neutral here… The current trial regarding former President Trump’s accounting practices may at least partly hinge on his motivations and there is a wide range of legal and layperson opinions on what those motivations may have been and when. Clearly, the effect of one motivation doesn’t preclude the possibility of other motivations. And the ranking of various motivations may change over time.

In this case, the Ethical Review Board said Jack’s political contribution is acceptable because it is nominal. Ok. What if the case was a little different, as often happens? What if the current County Board Chairman’s opponent was very opposed to Jack? Would Jack then be ethically permitted to contribute more to the current board chairman? How much more? Things get very complicated very quickly.

Since our country’s leadership is elected through the political process which requires monetary contributions to support candidates for office, disallowing poltical contributions would exclude professional engineers from a critical part of US citizenship.

Nominal contributions are therefore acceptable. The decision on what represents “nominal” includes many variables, such as the means of the donor (what a donor of considerable means considers nominal is different than others), as well as the impact of a certain value donation in different economic areas of the country.

In the current climate of political polarization and media reporting, any contribution could be made to appear as seeking favoritism and decried as bribery, if subsequent contract work is won. Perception should not be used as a criteria unless a legal violation has occurred.

While the implication drawn by the reporting may be valid, the law seems to have established the upper limits on “nominal.” I would argue that a contribution up to the legal limit would be ethical.

I hope the Ethical Review Board had a clothes-pin handy when they decided this case. Seems as though they arbitrarily decided on the acceptable nominal amount based upon the amount requested by the candidate compared to the amount given to arrive at the “ethical” conclusion. Or, since the salary received by the chairman and also the members was given in the facts, it may have been an acceptable amount based a percentage of the candidates salary for the position!

Why bother with stating the Code 11.5.b section if you omit, ” or which may be reasonably construed by the public as having the effect or intent of influencing the awarding of a contract”. I believe the media is the public’s eyes on political influence.

I agree fully with Mr. Newman. II.5.b is very clear: “They shall not offer ANY gift or other valuable consideration in order to secure work.” Half of his firm’s work comes from the county. It is in his economic interest to continue that relationship. This, at the very least, makes an appearance of impropriety. That means that the line for such contributions is ZERO. The purpose of political contributions – particularly those dollar amounts that have to be publicly reported – is access to the candidate when he/she becomes the incumbent. The engineer in question is already known to the candidate, they work together in the same political party. He already has access. He should have respectfully declined – stating that such contributions could be viewed as trying to influence the chairman and that he has an ethical obligation to not offer any gift or other valuable consideration that could be used to call his integrity into question.