This is the February 2022 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think? This series is comprised of case studies from NSPE archives, involving both real and hypothetical matters submitted by engineers, public officials and members of the public.

Your peers and the NSPE Board of Ethical Review have reviewed the facts of the case as shown below. And, here are the results.

Your opinion has been registered for the February 2022 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on February 22.

Your opinion has been registered for the February 2022 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on February 22.

A Review of the Facts

Engineer Greg, an environmental engineer employed by the state environmental protection division, is ordered to draw up a construction permit for the construction of a power plant at a manufacturing facility. He is told by a superior to move expeditiously on the permit and “avoid any hangups” with respect to technical issues. Greg believes the plans as drafted are inadequate in meeting the regulation requirements, and that outside scrubbers to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions are necessary, and without them, the issuance of the permit would violate certain air pollution standards as mandated under the 1990 Clear Air Act. His superior believes that plans which involve limestone mixed with coal in a fluidized boiler process would remove 90% of the sulfur dioxide and would meet the regulatory requirements. Greg contacts the state engineering registration board and is informed, based upon the limited information provided to the Board, that suspension or revocation of his engineering license was a possibility if he prepared a permit that violated environmental regulations. Greg refused to issue the permit and submitted his findings to his superior. The department authorized the issuance of the permit. The case had received widespread publicity in the news media and is currently being investigated by state authorities.

Was it ethical for Greg to refuse to issue the permit?

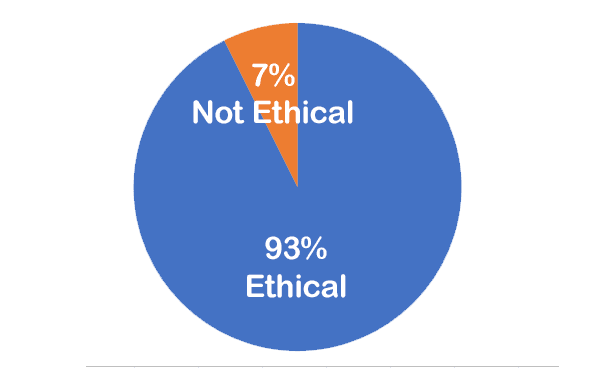

Here is the result of our survey of your peers:

Applicable NSPE Code References:

Code I.1

Hold paramount the safety, health and welfare of the public in the performance of their professional duties.

Code II.1.a

If engineers’ judgment is overruled under circumstances that endanger life or property, they shall notify their employer or client and such other authority as may be appropriate.

Code II.1.b

Engineers shall approve only those engineering documents that are in conformity with applicable standards.

Code II.3.a

Engineers shall be objective and truthful in professional reports, statements, or testimony. They shall include all relevant and pertinent information in such reports, statements, or testimony, which should bear the date indicating when it was current.

Discussion

The facts of this case are in many ways a classic ethical dilemma faced by many engineers in their professional lives. Engineers have a fundamental obligation to hold paramount the safety, health and welfare of the public in the performance of their professional duties (Code I.1). Moreover, the Code provides guidance to engineers who are confronted with circumstances where their professional reputation is at stake. Sometimes engineers are asked by employers or clients to sign off on documents in which they may have reservations or concerns.

The Board of Ethical Review has examined this issue over the years in differing contexts. As early as case BER 65-12, the Board dealt with a situation in which a group of engineers believed that a product was unsafe. The Board then determined that as long as the engineers held to that view, they were ethically justified in refusing to participate in the processing or production of the product in question. The Board recognized that such action by the engineers would likely lead to loss of employment.

More recently, in BER Case 88-6, an engineer was employed as the city engineer/director of public works with responsibility for disposal plants and beds and reported to a city administrator. After (1) noticing problems with overflow capacity, which are required to be reported to the state water pollution control authorities, (2) discussing the problem privately with members of the city council, (3) being warned by the city administrator to only report the problem to him, (4) discussing the problem again informally with the city council and (5) being relieved by the city administrator of responsibility for the disposal plants and beds by a technician, the engineer continued to work in the capacity as city engineer/director of public works. In ruling that the engineer failed to fulfill her ethical obligations by informing the city administrator and certain members of the city council of her concern, the Board found that the engineer was aware of a pattern of ongoing disregard for the law by her immediate supervisor as well as by members of the city council. After several attempts to modify the views of her superiors, the engineer knew or should have known that “proper authorities” were not the city officials, but more likely state officials. The Board could not find it credible that a city engineer/director of public works for a medium-sized town would not be aware of this basic obligation. Said the Board, the engineer’s inaction permitted a serious violation of the law to continue and made the engineer an “accessory” to the actions of the city administrator and others.

Turning to the facts of this case, we believe the situation involved in this case is in many ways similar to the situation involved in BER Case 88-6. However, unlike the circumstances involved in BER Case 88-6, where the issues were hidden from public view, here, the case involves facts that have received coverage in the media. In view of this fact, we do not believe it is incumbent upon Greg to bring this issue to the attention of the “proper authorities.” As we see it, such officials are already aware of the situation and have begun an investigation. The reason for our position in BER Case 88-6 was that the engineer’s failure to bring the problems to the attention of the “proper authorities” made it more probable that danger would ultimately result to public health, safety and welfare. Here, the circumstances are presumably already known to appropriate public officials. To bring the matter to their attention is a useless act.

However, we believe it would have been unethical for Greg to withdraw from further work on the project because Greg had an obligation to stand by his position consistent with his obligation to protect the public, health, safety and welfare and refuse to issue the permit. Engineers have an essential role as technically qualified professionals to “stick to their guns” and represent the public interest under the circumstances where they believe public health and safety is at stake.

We would also note that this case also raises another dimension which involves the role of the state licensing board in determining the ethical conduct of licensees. Under the facts, Greg affirmatively sought the opinion of the state as to whether his approval of the permit could violate the state engineering registration law. We believe Greg’s actions in this regard constitute appropriate conduct and actions are consistent with Code II.1.a. This case involves a question of public health and welfare and Greg’s decision to disassociate himself from further work on this project avoids having Greg being placed in a professionally compromising situation.

The Ethical Review Board’s Conclusion

It was ethical for Greg to refuse to issue the permit.

BOARD OF ETHICAL REVIEW

William A. Cox, Jr., P.E. William W. Middleton, P.E. William E. Norris, P.E., William F. Rauch, Jr., P.E. Jimmy H. Smith, P.E. Otto A. Tennant, P.E., Robert L. Nichols, P.E., Chairman

Note – In regard to the question of application of the Code to corporations vis-a-vis real persons, business form or type should not negate nor influence conformance of individuals to the Code. The Code deals with professional services, which services must be performed by real persons. Real persons in turn establish and implement policies within business structures. The Code is clearly written to apply to the Engineer and it is incumbent on a member of NSPE to endeavor to live up to its provisions. This applies to all pertinent sections of the Code. This opinion is based on data submitted to the Board of Ethical Review and does not necessarily represent all of the pertinent facts when applied to a specific case. This opinion is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as expressing any opinion on the ethics of specific individuals. This opinion may be reprinted without further permission, provided that this statement is included before or after the text of the case.

Greg should seek the opinion of an outside consultant to confirm or deny his position. Refusing to issue the permit is the easy route out of this predicament. PEs should be prepared to take the difficult route even if it means losing their job.

I think the case information as presented was too vague and did not provide a solid technical basis for Greg to “believe” that the alternate process would not work that his superior “believed” would work. As professionals, we need to see the data, review process analysis, and have the Permitee provide supporting information, data, studies, etc. in support of their proposal. As presented, this case involved two professionals that apparently did not agree on the “belief” each had on which process would meet the Regulatory criteria. If a superior, presumably a qualified one, thinks the proposed process is appropriate and will work, then I feel it unethical for his subordinate to disagree without data to back it up, especially to the point Greg refused to do his job and even went to the Board. Maybe I’m looking at this too closely, but having been in both positions as Greg and his superior, I think the situation needs to first be addressed by them at the technical level and mutual agreement on how to move forward reached. Here we are assuming the superior did something wrong, but I don’t see it. What I see is a subordinate not agreeing with a superior on a technical matter, not a legal one. If you told me his superior was not an engineer and simply an administrator, then maybe I could see it, but that wasn’t said here I don’t think. Ultimately, the Permit will require the holder to prove the process used works, as they will need to meet certain regulatory standards based on required testing, performance goals, and compliance conditions. If they cannot, then the Permittee is in violation and needs to upgrade the system accordingly to meet the standards, otherwise, face fines and possible loss of Permit. Again, the proposed process either works or it doesn’t and, based on “technical considerations and facts” not beliefs the Permit should or should not be issued. Maybe there is another lesson to be learned here.

curious at the end , the DEPARTMENT approved the permit. Greg worked for the division. So who approved the permit?

The biggest issue here may be, Is the law 100% accurate? So much of our environmental law has been established by legislators; many of whom lack the knowledge to determine the accuracy of the information they receive from technical experts. Sometime these experts represent special interests. So, It may be that real un-ethical individuals were the technical experts, their sponsors or, the legislators.

I would think that before Greg denies the permit he would meet with the superior to discuss their technical differences of opinion as well as point out the obvious violation of environmental regulations. Sounds like the superior also has some knowledge that Greg may not be considering. Perhaps this would have prevented media attention will end up giving “black eyes” to the permittee, and the agency.

As I see it, the hook here is the information that “He is told by a superior to move expeditiously on the permit and “avoid any hangups” with respect to technical issues.” This implies something shady is going on and that the supervisor has more information, perhaps not proven or well developed, and knows that the project would likely not qualify for a permit. Greg seems to have confirmation that the proposed process would not meet regulatory requirements.

I was caught up in a project from an overseas company that wanted to build a Biogas plant in the US. I was hired as their PM. I had just completed several projects for a municipality in Georgia that were huge successes.

This project started poorly and went downhill rather quickly. The company did very little researching of such a project in the US, especially for needed permits, designs requiring engineer seals, and approvals from the state regulatory agencies. The company that owned the project worked together with a sponsoring company that held the majority of the financing. As problems developed and it was soon after starting the project, I could already see the handwriting on the wall. I lasted a little over a year before the project crumbled. The sponsor tried to blame me, but the owner company took the blame. The sponsor hired another PM to try and save the project, however it was not going to happen. They asked to have me fired, but I resigned knowing I had never been fired from any organization in my 30 plus years of work.

Needless to say, they built the Biogas plant with a $10 million exceedance of the budget, but it is nothing more than a tombstone today. It has never produced one watt of power. During my tenure, they tried unsuccessfully to get me to sign an engineering document that I had nothing to do with producing. That was when I resigned. I knew I did the right thing and I went on to other successful projects soon after. These ethical situations are very helpful to newer engineers that may not know how to navigate the business world. It is much better to leave something that isn’t going to work, than to lose a career.

The discussion of this case is a little light on information. Greg better have some iron clad analysis and calculations for his position, as it seems he has either his license or his job on the line. The right thing here is to choose preserving his license. Thanks to the perks and benefits of long term employment at a government agency it can be a very difficult decision for him, as the level of continued employment uncertainty that exists in many engineering fields in private employment would be virtually unknown to him. It gets down to the point that he must have the backbone and determination to do the right thing regardless of apparent cost. If he is uncomfortable about the case but can’t prove it, he better have on record as strong a report for his position as he can manage for the sake of keeping his license and avoiding becoming one of the defendants in legal action brought by environmental groups. Should this cost6 him his job, that is still the better choice. Losing his license could well cost him his job anyway, so agreeing to go along with his supervisor could result in him being considered as part of the wrong doing, as well, so there is no obvious up side to going along with his supervisor.

As others have pointed out, the technical disagreement between Greg and his superior is somewhat central to the entire fact pattern. The fluidized bed process with limestone either will or will not meet the regulatory requirements. Had the description contained information to the effect that the alternate technology was experimental or had never been through a pilot demonstration program or sufficient documentation as to its effectiveness couldn’t be supplied, then Greg would be on much firmer ground. What tips the scales is that Greg went to the state engineering registration board and proactively secured their opinion. We might reasonably assume that the discussion with the board included sufficient technical detail for the board to make the recommendation it did.