This is the October 2024 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think? This series is comprised of case studies from NSPE archives, involving both real and hypothetical matters submitted by engineers, public officials, and members of the public.

Your peers and the NSPE Board of Ethical Review have reviewed the facts of the case as shown below. And, here are the results.

Your opinion has been registered for the October 2024 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on

October 22.

Your opinion has been registered for the October 2024 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on

October 22.

A Review of the Facts

Engineer Annie is retained by an architect to provide mechanical engineering services in connection with the design of a small office building. Annie performs her services and thereafter a dispute arises between Annie and the architect as to Annie’s final compensation for her services. The issue is never finally resolved. Several months later, the owner, who retained the architect on the project, requested that Annie provide him with a copy of the final record drawings in order to perform certain work on the building which does not involve issues of safety or health. The owner offers to pay Annie the cost of reproduction and any administrative staff costs and to attempt to mediate the dispute between Annie and the architect. Annie refuses to provide the owner with a copy of the drawings and declines the owner’s offer to mediate the dispute.

What Do You Think?

Was it ethical for Annie to refuse to provide the owner with a copy of the drawings and to decline the owner’s offer to attempt to mediate the dispute between Annie and the architect?

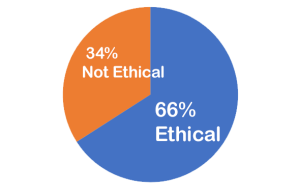

Here is the result of our survey of your peers:

Applicable NSPE Code References:

I.1

“Engineers, in the fulfillment of their professional duties, shall hold paramount the safety, health and welfare of the public.”II.4

“Engineers shall act for each employer or client as faithful agents or trustees.”

Discussion

The facts presented in this case touch upon a sensitive ethical issue faced by engineers-what are the third-party ethical responsibilities of the engineer who is involved in a contract dispute?

The NSPE Code of Ethics is patently clear in Code I.1, but that language, standing alone, does not provide a significant amount of guidance to us in considering the facts before us. The language in Code II.4, on its face, does not provide much clarity to us in the context of this case because it is unclear whether the engineer has an ethical obligation to the owner who is neither an employer nor a client under the facts.

While the Board has heretofore not addressed a case such as this, we have addressed at least one case that might provide us with some direction. In Case 67-3, Engineer X was retained by a municipality to prepare plans and specifications for a comprehensive sanitary sewer program. After approximately 80 percent of the total project was constructed in subsequent years, Engineer X’s contract was terminated and he was paid in full for his services.

Ten years later, the municipality retained another engineer to revise and update the plans and specifications prepared by Engineer X. The municipality requested Engineer X to provide it with originals or copies of the plans and specifications that Engineer X had in his possession, offering to pay Engineer X the cost of reproduction. Engineer X refused to comply with the request. The original contract was silent as to ownership of the plans and specifications, but did contain a clause stating that: “If the City requires more than six complete sets of final plans, specifications, and documents, the Engineers agree to provide any number of additional copies for no more than blueprinting, mimeographing and mailing costs.”

In finding that Engineer X was ethically obligated to provide the originals or copies of the plans to the municipality, the Board noted that as a general rule in the absence of a contract provision on ownership of plans, the plans and contract documents are the property of the client. Moreover, we noted that Engineer X’s refusal to cooperate will put the municipality at unnecessary additional expense to the extent that the second engineer would be required to expend additional time to investigate the work done under the earlier contract as related to the work to be performed. We noted that this situation would not be in accord with the mandate of the Code in that Engineer X was not regarding his duty to the public welfare as a paramount consideration. Of considerable note, the Board concluded by stating: “Under the (original) contract, Engineer X was obligated to furnish additional copies of the plans to the client upon request. The fact that the contract is now terminated, regardless of the legal position of the parties, should not be used by him as a means of technical avoidance of his ethical obligation to serve the interests of the client without any cost to Engineer X. The ethical duty is supported by the dictate Code 1.”

Under the facts of the instant case, it is clear that Annie was retained by the architect and not the owner. From a purely technical standpoint, therefore, it was the architect and not the owner who was the “client” and arguably any potential ethical obligations owed by Annie to a “client” were owed to the architect and not to the owner. However, this preliminary conclusion has to be weighed against other circumstances which take into consideration other provisions of the Code of Ethics and the practical realities of professional relationships.

First, as we noted in Case 67-3 as a general rule, in the absence of a contractual provision to the contrary, the drawings, plans, and specifications prepared by an engineer for a client are the property of the client. While we are mindful of our preliminary conclusion that technically, it was the architect and not the owner who was the “client” of the engineer, we believe the Code should be read flexibly, particularly where the service being rendered by the engineer is being incorporated into a larger design plan for the benefit of a client. In this larger context, the term “client” should be interpreted more broadly to encompass the owner-the ultimate “beneficiary” of the services that Annie has been retained to provide, and the one who, however indirectly, has provided compensation for her services.

In addition, as noted in Case 67-3, there exist additional professional obligations of which Annie must be mindful. Annie’s refusal to provide the owner with copies of the drawings until her dispute with the architect is resolved could potentially jeopardize the economic value of his building. Placing the jeopardy in this manner contravention of Ethics.

Finally, we are troubled by Annie’s arbitrary refusal of the owner’s offer to mediate the dispute between Annie and the architect. Neither Annie’s interest in a resolution of her dispute with the architect nor the owner’s interest in obtaining a copy of the record drawings were well served by her refusal. Annie’s refusal was neither within the letter nor the spirit of Code II.4 of the Code of Ethics.

The Ethical Review Board’s Conclusion

It was unethical for Annie to refuse to provide the owner with the drawings and to decline owner’s offer to attempt to mediate the dispute between Annie and the architect.

BOARD OF ETHICAL REVIEW

Eugene N. Bechamps,; Robert J. Haefeli, P.E.; Robert W. Jarvis, P.E.; Lindley Manning, P.E.; Paul E. Pritzker, P.E.; Harrison Streeter, P.E.; Herbert G. Koogle. P.E, L.S., chairman

Note – In regard to the question of application of the Code to corporations vis-a-vis real persons, business form or type should not negate nor influence conformance of individuals to the Code. The Code deals with professional services, which services must be performed by real persons. Real persons in turn establish and implement policies within business structures. The Code is clearly written to apply to the Engineer and it is incumbent on a member of NSPE to endeavor to live up to its provisions. This applies to all pertinent sections of the Code. This opinion is based on data submitted to the Board of Ethical Review and does not necessarily represent all of the pertinent facts when applied to a specific case. This opinion is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as expressing any opinion on the ethics of specific individuals. This opinion may be reprinted without further permission, provided that this statement is included before or after the text of the case.

“we believe the Code should be read flexibly”

Well doesn’t that open a huge can of worms.

To the contrary the Architectural Works Copyright Protection Act 1990 the Designer is the owner that is letting the owner use for one time their work. Also the owner must have had plans to pull the building permit so why do they need drawings unless the engineer was contracted to the as-builts. The Engineer made the determination that the Engineer and Architect were engaged in illegal or dangerous activities that present a risk to the life and safety of others and stopped supporting such actions to prevent liability. Case 67-3 dates to 1958.

We also do not know the details around the dispute which arose for her “services in connection with the design of a small office building”. There could be several various examples where these “services” / scope of work could be non-trivial, including potential use of proprietary or IP developed by Annie which she or her firm owns…

Depending on the circumstances, her refusal could be Ethical…

I believe the engineer would own the copyright for these plans. If the property Owner, or even a new Owner, need the original plans, they can rely on the permit plans which become public record. Use of those plans for a second project are not legal.

It sounds like the architect never finished paying Annie, so the drawings are not their property yet. There’s no reason Annie shouldn’t hold onto them until she is paid in full.

It is my opinion that Annie was unprofessional and possibly not very prudent, but not unethical. Since there is a dispute under the contract, it may be reasonable to not provide the documents. A contract is a “This” for “That” and if one is unsatisfied, so is the other (possibly). Without more detail, it is difficult to determine if her reasons for not cooperating are well founded or not. These drawings may be the only piece of leverage that Annie has. If she is an ethical person, she should pursue mediation for fair compensation for her services both past and future. Requesting anything more would be unethical and a form of extortion. Finding common interest in resolving a contract dispute outside of a court should be appealing to her. Especially since Annie may be holding all the cards. I’m not sure why she would not cooperate with the possibility of having the original contract fulfilled to her expectations.

I was once in a very similar situation where an architect refused to pay me for engineering services after signed CDs were issued. The owner later came to me for electronic versions of the drawings. A deal was worked out where I was able to receive full payment and I delivered the files directly to the owner. It was a win for each of us…I’m not sure I can say the same for the architect as they were the ones being unethical and are no longer a business entity.

I tend to agree with John Kelly – without knowing the details of the contract and the disagreement, it’s difficult to decide whether the actions were actually unethical – but I’d say they weren’t wise or polite.

I agree with others that Annie is in the right. She has an agreement with the Architect, not the owner. The owner has no standing in the dispute. Annie has no obligation to the owner regardless if the owner is trying to pay or mediate the dispute. It’s the Architect that is responsible for settling with Annie, or finding another engineer.

I believe that this is a question of good business practice, not ethics. Annie’s client is the Architect, not the owner. If the Owner wanted a position to demand drawings from Annie’s firm, they needed to contract directly with her firm or include a statement of ownership in their contract with the Architect.

The Owner should press the Architect to conform to their contract with the owner, and turn over the drawings required by the contract.

We don’t know all of the details, but I think I would turn over the drawings as a means to gain good will with a potential client.

I agree with other posted comments – the case as presented does not include enough information to determine if Annie’s actions are unethical. She is within her rights to withhold her intellectual property from a third party. That may not be wise if she wants to do business with the owner in the future. And we don’t know enough about the dispute between Annie and the architect. Annie again is fully within her rights (and ethics) to decline meddling from an interested party.

Drawings and specifications are Instruments of Service and are the property of the Design Professional unless specifically stated otherwise in a design contract. The owner only owns the results of the construction. Annie is within her rights to not give away her instruments of service unless she is paid.

The comparison to the municipal project is not applicable to the facts of this case. In the municipal project, the engineer was compensated, creating an obligation to provide the plans. However, in Annie’s case, she was not fully compensated and is therefore under no obligation to provide any plans without appropriate payment.

The Board may use a very liberal interpretation of the rule and claim it wasn’t ethical, but i’m sure a judge would see it differently.

The Owner’s legal, contractual relationship is with the architect. Their request for drawings should have been submitted to the architectural firm. They have no business involving themselves in the dispute between their direct supplier or general contractor – the architect – and their supplier’s subcontractor – the engineer. Doing so violates legal privity between the architect and their hired subcontractor. Well-meaning but careless Owners frequently tread across this boundary, causing all manner of problems. The most frequent problem is scope creep: the Owner asks the subcontractor for some design change, without the general contractor’s knowledge of the change. If the engineer does as requested and provides the additional services, she is likely not to be paid by the general contractor, who did not have opportunity to evaluate or agree with the change. Then typically the Owner fails to issue a field order covering the additional expense to the general contractor. That lack of funding rolls downhill to the engineer, who doesn’t get paid for the additional work. Annie’s response may have been unprofessional, but still ethical. A professional response would have been to tell the Owner to present their request for drawings to the architect, or to offer to make that presentation on their behalf, since they are the responsible party to provide that service to the Owner. In that situation, Annie actually gains some leverage in her dispute with the architect, because the Owner has a contractual relationship with the architect and can refuse to pay them until the requested drawings are delivered, which should inspire the architect to settle with Annie in order to be paid for the overall job.

+1 on Geargrinder’s comments. Annie’s contract is with the architect, not the owner.

In this case I don’t see any danger to public health or safety by Annie’s refusal to deliver the drawings to the Owner. Therefore, Annie was within her rights to hold onto the drawings and did nothing unethical.

There is no reason why Annie should be expected to accept the offer of mediation by the owner. The owner is not a professional mediator, and there is no indication that the owner’s opinion would be fair and impartial. The owner may be a friend of the architect, and therefore biased. It is unreasonable for the board to be “troubled” by Annie’s refusal of this person’s offer of mediation.