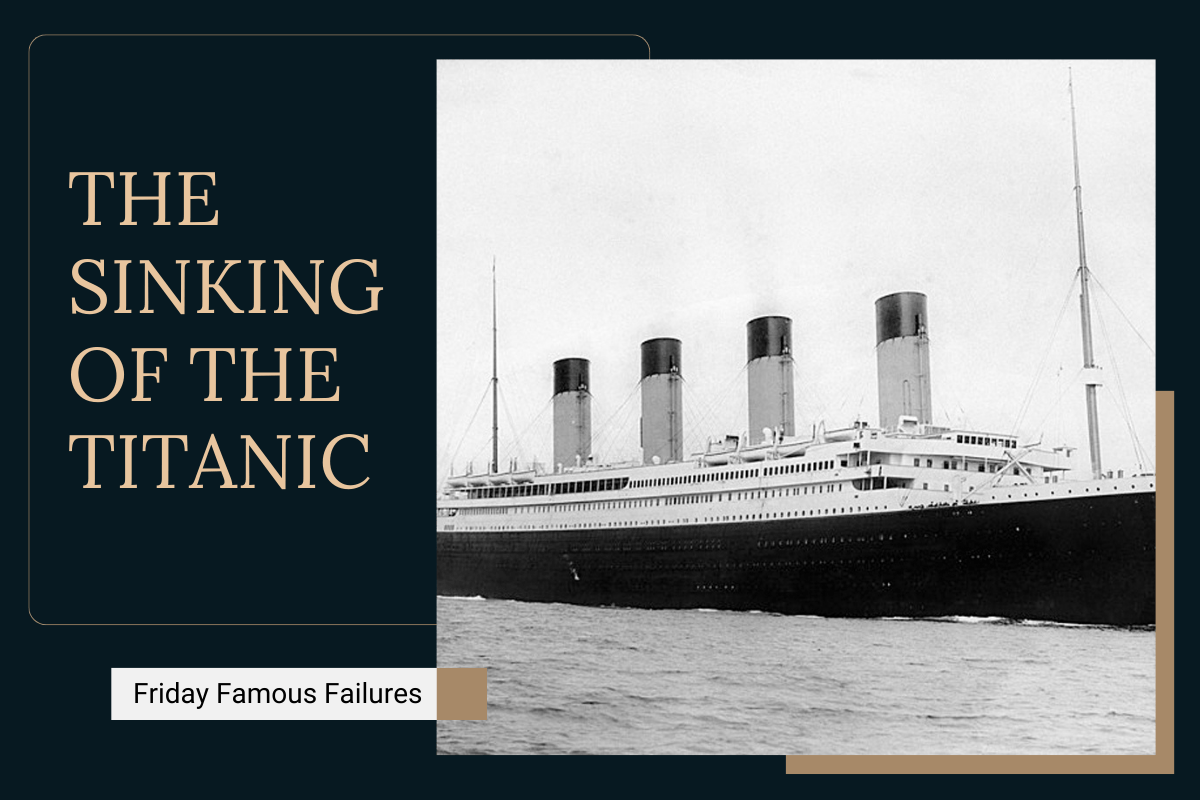

It’s an old adage that sometimes the unthinkable happens. Well, sometimes the unsinkable happens too. In the early morning hours of April 14, 1912, the largest luxury passenger liner ever built, the R.M.S Titanic, struck an iceberg in the frigid Atlantic Ocean. The impact was devastating. Icy water rushed into the lower levels of the ship, the pumps could not keep up, and the ship sank, killing more than 1,500 people.

It was the Titanic’s maiden voyage. Advances in shipbuilding and the ship’s large size led to the belief that she was “virtually unsinkable.” Her captain, Edward John Smith, proclaimed, “I cannot imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder. I cannot conceive of any vital disaster happening to this vessel. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that.” The Titanic’s builders asserted that even if the Titanic collided with another ship, it would stay afloat for at least two to three days, which would allow all the passengers to be rescued. They were all wrong; the Titanic sank within two hours and forty minutes of striking an iceberg.

The Titanic was an ocean liner owned by White Star Lines and built by Harland and Wolff, a prestigious Irish shipbuilding company in Belfast, Ireland. This shipyard was considered the leader in shipbuilding and advanced the most modern design, technology, and safety features in marine engineering. This led to a false sense of security in the ship’s operators.

At the time of her construction, the Titanic was the largest moving object ever built, measuring 882.9 feet long, 92.5 feet wide, and 174.9 feet tall. The ship had ten decks, eight for passengers and two for cargo and ship functions. At full capacity, the ship could carry 2,453 passengers and 1,094 crew members, for a total of 3,547 people. The Titanic had the most modern features afloat, including a fully equipped gym, libraries, the first heated swimming pool on a ship, fine dining, an infirmary, and even a state-of-the-art Marconi wireless radio.

The Titanic’s maiden voyage began on April 10, 1912, in Southampton, England. The captain, Edward J. Smith, had been with White Star lines for over twenty-two years and was their most senior Captain. The Chief Officer, Henry Wilde, began his career with White Star in 1897 as a junior officer and had been with the company for fifteen years.

The voyage was uneventful until the afternoon of April 12, when the French liner, La Touraine, sent a radio warning of ice in the steamship lanes. These warnings continued and on April 14, the Titanic received at least six messages about icebergs and ice fields in her course. In response, Captain Smith altered course south and maintained a cruising speed of 22.5 knots. However, he also canceled scheduled lifeboat drills that day.

Timeline of the Accident:

- 8:10 pm: The Titanic received a radio warning of icebergs from the SS California.

- 9:00 pm: Captain Smith discussed the situation with his Second Officer and at 9:20 pm, he retired to his quarters.

- 9:30 pm: the First Officer told lookouts in the crow’s nest (95 feet above the water line) to watch for icebergs.

- 9:40 pm: The Titanic received yet another radio message about icebergs from the SS Mesaba, which was not taken to the bridge.

- 10:00 pm: the First Officer relieved the Second Officer; the crew on the forward watch are also warned to look for small icebergs, but no crewmembers have binoculars.

- 10:50 pm: the SS California, stopped in the water at the edge of the ice field, saw the Titanic on the horizon roughly 19 miles away, and radioed another warning, but the Titanic’s wireless operator ignored the transmission.

- 11:39 pm: A lookout spotted the iceberg, sounded the alarm, and telephoned the bridge, “Iceberg, right ahead!” The First Officer ordered, “Stop! Full Speed astern!”

- 11:40 pm: Just 37 seconds after sighting the iceberg, the Titanic struck the iceberg near the bow on the starboard side.

- 11:47 pm: The Titanic is stopped in the water. Captain Smith directed wireless operators to prepare a distress call. Inspections determined that 14 feet of water had entered the first four watertight compartments of the ship and eight feet of water had entered the fifth compartment. Although the wireless operator issued a call at 12:04, the initial position was incorrect. Two ships acknowledged the radio transmission but the SS. California, only 12 miles away, had turned off its wireless at 11:30 pm and did not receive the message.

- 12:45 am. The first lifeboat, Boat 7, launched with mostly women and was not filled to capacity. One passenger, a Colorado socialite, earned the nickname, “The Unsinkable Molly Brown” after she encouraged the women to row and tried to turn the boat back to collect passengers in the water. More lifeboats were launched as the Titanic began to sink, but they were also not filled to capacity.

- 2:20 am: Two hours and forty minutes after the collision with the iceberg, the Titanic sunk into the ocean. The SS Carpathian picked up the 770 survivors by 8:30 that morning.

While the primary cause of the sinking was striking the iceberg and rupturing the first five watertight compartments on the starboard side bow, other contributing factors included:

Conditions:

- There was a large ice field along the Titanic’s course.

- The winter of 1911-1912 was the mildest in over 30 years, causing more icebergs than usual.

Ship operations:

- Lack of binoculars. There were only five pairs of binoculars aboard the Titanic, and the lookouts were not using them.

- Excessive speed. It is likely that Smith was trying to achieve the fastest crossing of the Atlantic Ocean to increase publicity and to notch a final success before retirement. However, at 22.5 knots, the Titanic could not easily stop or turn.

- Poor ship handling. Although the iceberg was sighted too late for the Titanic to stop before hitting it, it may have been able to turn in time if he had reversed the port engine.

- Poor crew readiness. Due to the lack of crew training on evacuation procedures and the fact that no lifeboat drill was ever conducted during the voyage, most of the lifeboats launched less than a full complement of passengers. Ultimately, there were 473 empty seats on the Titanic’s lifeboats.

Ship Design:

- Poor quality materials. Researchers analyzed hull steel that was recovered from the ship and found that the hull plates may have buckled due to elastic-plastic deformation. Other contributing factors to the steel hull failures were stress concentrations from small cracks at the rivet holes, possibly caused by punching rather than drilling the rivet holes. Additionally, a 1998 expedition found empty rivet holes near hull plate joints, suggesting that the rivets had failed and the overlapping joints separated, which would have significantly contributed to the hull failure and hastened the sinking.

- Lack of sufficient lifeboats. The Titanic was carrying 2,224 passengers and crew members but only had lifeboat space for 1,178 people. Although the ship could have fit 64 lifeboats on the ship capable of carrying 3,547 passengers, chief designer Alexander Carlisle originally planned for only 48 and later reduced the number to 20 to avoid alarming passengers and crowding the top deck. This was not illegal at the time as regulations required that all vessels over 10,000 metric tons carry a minimum of 16 lifeboats.

- Partial bulkheads. The ship sank so quickly because of the height of its bulkheads, and the upright partitions positioned within the hull to stop any breaches from flooding the rest of the ship. The Titanic’s bulkheads did not reach the deck above, extending only 10 feet above the waterline. When it struck the iceberg, five of Titanic’s 16 compartments breached, causing the bow to dip, which in turn forced water into the remaining compartments.

As a result of the Titanic disaster, the Titanic’s builders Harland and Wolff extended the height of the bulkheads of the sister ships, HMHS Britannic and RMS Olympic, made them fireproof, and also fitted a second internal hull to make both more impact-resistant. Ships’ bulkheads also became watertight on all sides by stretching from deck plate to deckhead (floor to ceiling).

The tragedy of the Titanic led to the first International Convention for Safety of Life and Sea (SOLAS) in 1913. The resulting treaty, signed in 1915, required that ships have enough lifeboats to provide seats for all passengers and crew members plus 25%. The treaty also mandated lifeboat drills and that all lifeboats carry sails, signaling devices, food, water, and oars. The convention further required ships to maintain a 24-hour radio watch with backup power to prevent missed distressed calls and to respond to distress calls. It also standardized the firing of red rockets as a distress call. It also required ships to either maintain a moderate speed or alter course if ice was reported near the ship.

The tragedy of the Titanic changed the course of sea travel and serves as a stark reminder that no matter how strong or big or powerful, human error and arrogance can sink even the unsinkable.

One thing we do now that wasn’t done in 1912 is practice emergency scenarios in simulators. The crew may have been able to avoid the iceberg if differential thrust had been applied, with the starboard engine in full forward thrust, the port engine in full aft thrust and the rudder hard over to port, rather than “stopping” and putting both engines in full thrust astern. It is likely that the crew never practiced such a maneuver. Beyond that, traveling through a known ice field at 22.5 Kts at night (before radar existed) and relying on Lookouts with no binoculars for obstacle avoidance seems like hubris on steroids.

I recall reading about two other contributing factors.

First, the Titanic’s rudder was small for a ship of its size. That reduced its ability to turn, in this case fatally so. Indeed, it appears that the iceberg collision was a glancing blow and just a few more feet of turn could have made all the difference.

Second, modern examination of the Titanic’s steel showed the presence of sulfide stringers. This greatly reduced her steel’s elasticity when cold, such as in near-freezing sea water, making it less ductile. One of my college metallurgy textbooks had a picture of a WWII Navy oil tanker that ruptured in half at the dock in Alaska due to the combined effects of sulfide stringers, cold temperatures and stress. (BTW, the steel samples came from some of Titanic’s rivet punchouts which had become souvenirs and paperweights.)