This is the September 2021 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think? This series is comprised of case studies from NSPE archives, involving both real and hypothetical matters submitted by engineers, public officials and members of the public.

Your peers and the NSPE Board of Ethical Review have reviewed the facts of the case as shown below. And, here are the results.

Your opinion has been registered for the September 2021 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on September 28.

Your opinion has been registered for the September 2021 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on September 28.

A Review of the Facts

Engineer Charles is retained by Client B to perform design services and provide a Critical Path Method (CPM) schedule for a manufacturing facility. Charles prepares the plans and specifications and the CPM schedule.

During the rendering of services to Client B on this project, the state board of professional engineers contacts Charles regarding an ethics complaint filed against Charles by Client C relating to services provided on a project for Client C that are similar to the services being performed for Client B.

Client C alleges that Charles lacked the competence to perform the services in question. Charles does not believe it is necessary to notify Client B of the pending complaint. Later, through another party, Client B learns of the ethics complaint filed against Charles and tells Charles that he is upset by the allegations and that Charles should have brought the matter to Client B’s attention.

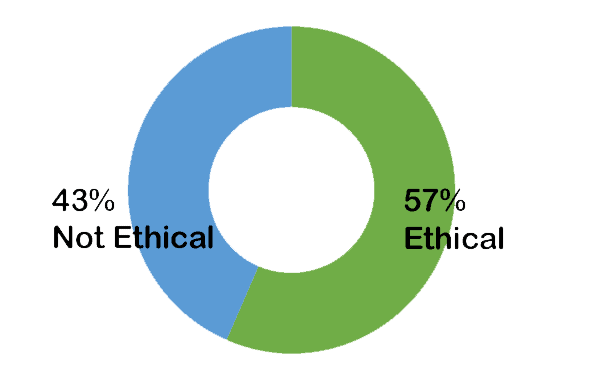

Charles did not report to Client B the ethics complaint filed against him by Client C. Was that an ethical decision?

Here is the result of our survey of your peers:

Applicable NSPE Code References:

Code II.3.a: Engineers shall be objective and truthful in professional reports, statements, or testimony. They shall include all relevant and pertinent information in such reports, statements, or testimony, which should bear the date indicating when it was current.

Code II.4.a: Engineers shall disclose all known or potential conflicts of interest that could influence or appear to influence their judgment or the quality of their services.

Code II.5.a: Engineers shall not falsify their qualifications or permit misrepresentation of their or their associates’ qualifications. They shall not misrepresent or exaggerate their responsibility in or for the subject matter of prior assignments. Brochures or other presentations incident to the solicitation of employment shall not misrepresent pertinent facts concerning employers, employees, associates, joint ventures, or past accomplishments.

Code III.3.a: Engineers shall avoid the use of statements containing a material misrepresentation of fact or omitting a material fact.

Discussion

The obligation of the engineer to be honest and truthful and to avoid acts that might be viewed as misleading and deceptive is clearly stated in various sections of the NSPE Code of Ethics (See Code II.3.a., Code II.4.a, Code II.5.a. and Code III.3.a.).

The Board has reviewed a number of factual situations over the years relating to the question of misleading clients through the misrepresentation of professional qualifications. For example, in Case No. 83-1, Engineer A worked for Engineer B. Engineer B notified Engineer A that Engineer B was going to terminate Engineer A because of lack of work. Engineer A continued to work for Engineer B for several additional months after the termination notice. During that period, Engineer B distributed a previously printed brochure listing Engineer A as one of Engineer B’s key employees and continued to use the previously printed brochure with Engineer A’s name in it well after Engineer B did in fact terminate Engineer A.

The Board ruled that it was not unethical for Engineer B to distribute a previously printed brochure listing Engineer A as a key employee, providing Engineer B apprised the prospective client, during negotiation, of Engineer A’s pending termination. The Board also ruled that it was unethical for Engineer B to distribute a brochure listing Engineer A as a key employee after Engineer A’s actual termination.

Interpreting the meaning of Code II.5.a, we noted that the words “pertinent facts” are those facts that have clear and decisive relevance to a matter at hand. Another way to characterize pertinent facts is as those that are “relevant and highly significant.” We determined whether (1) Engineer B in fact misrepresented “pertinent facts” and (2) whether it was the intent and purpose of Engineer B to “enhance the firm’s qualifications and work.” We noted that both factors must be present for a violation of Code II.5.a to exist.

In Case No. 90-4, Engineer X was employed by Firm Y, a medium-sized engineering consulting firm controlled by Engineer Z. Engineer X was one of the few engineers in Firm Y with expertise in hydrology, but the firm’s work in the field of hydrology did not constitute a significant percentage of the firm’s work.

Engineer X, an associate with the firm, gave two weeks’ notice of her intent to move to another firm. Thereafter, Engineer Z, a principal in Firm Y, continued to distribute a brochure identifying Engineer X as an employee of the firm and list Engineer X on the firm’s resume. After reviewing the facts, the Board concluded that it was not unethical for Engineer Z to continue to represent Engineer X as an employee of Firm Y under the circumstances described. Considering the earlier cases, the Board noted that the facts in Case No. 90-4, while similar, are different in one important area. In Case No. 83-1, Engineer A was highlighted in the firm’s promotional brochure as a “key employee.”

However, there is no suggestion in Case No. 90-4 that any of the brochures or other promotional material described Engineer X as a “key employee” in the firm. Nor is there any effort or attempt on the part of Firm Y to highlight the activities or achievements of Engineer X in the field of hydrology. While the facts reveal that Engineer X is one of the few engineers in the firm with expertise in the field of hydrology, Engineer X is not the only engineer in the firm who possesses such expertise. In addition, it appears that this area of practice does not constitute a significant portion of the services provided by Firm Y; therefore it would seem to us that the inclusion of the name of Engineer X in the firm’s brochure and resume would not constitute a misrepresentation of “pertinent facts.”

The facts in the present case are somewhat different than those involved in BER Case Nos. 83-1 and 90-4, because the earlier cases involved efforts by an engineering firm to enhance the firm’s credentials by implying that the firm had a higher level of expertise than it actually had. In contrast, the present case involves a situation that could reflect negatively on Charles and his firm. However, the Board does not believe the nature of the information—whether positive or negative—is at issue. The issue of greatest importance in each of these cases appears not to be whether a client would be pleased or disappointed with the information, but whether the information communicated (or in the present case not communicated) amounts to an act that misleads or deceives the client.

The Board is of the opinion that while an engineer clearly has an ethical obligation to act as a faithful agent and trustee for the benefit of a client, avoid deceptive acts, be objective and truthful, avoid conflicts, etc., such obligations would not compel an engineer to automatically disclose that a complaint had been filed against the engineer with the state engineering licensure board. A complaint is a mere allegation and does not amount to a finding of fact or conclusion of law. No engineer should be compelled to disclose potentially damaging allegations about his professional practice—allegations that could be false, baseless, and motivated by some malicious intent. Instead, Charles should weigh all factors and, depending upon the nature and seriousness of the charges, take prudent action, which might include providing Client B with appropriate background information.

On this last point, while the Board is not suggesting that Charles had an ethical obligation to report to Client B the ethics complaint filed against him by Client C, the Board believes Charles should have weighed providing Client B with some limited background information in a dispassionate and nonprejudicial matter for the benefit of all concerned. By doing so, Charles would be providing Client B with early notice of the pending matter so that Client B will be able to respond to comments or questions by third parties and would be demonstrating to Client B that Charles is acting in a professional and responsible manner and has nothing to hide or fear concerning the complaint.

The Ethical Review Board’s Conclusion

It was ethical for Charles not to report to Client B the ethics complaint filed against Charles by Client C.

BOARD OF ETHICAL REVIEW

James G. Fuller, P.E.; William E. Norris, P.E.; Paul E. Pritzker, P.E.; Richard Simberg, P.E.; Jimmy H. Smith, P.E., Ph.D.; C. Allen Wortley, P.E.; Donald L. Hiatte, P.E., Chairman

Note – In regard to the question of application of the Code to corporations vis-a-vis real persons, business form or type should not negate nor influence conformance of individuals to the Code. The Code deals with professional services, which services must be performed by real persons. Real persons in turn establish and implement policies within business structures. The Code is clearly written to apply to the Engineer and it is incumbent on a member of NSPE to endeavor to live up to its provisions. This applies to all pertinent sections of the Code. This opinion is based on data submitted to the Board of Ethical Review and does not necessarily represent all of the pertinent facts when applied to a specific case. This opinion is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as expressing any opinion on the ethics of specific individuals. This opinion may be reprinted without further permission, provided that this statement is included before or after the text of the case.

I disagree with Board’s decision. First, as they stated Charles should have “weighed providing Client B with some limited background information in a dispassionate and nonprejudicial matter for the benefit of all concerned”, i.e., he should have let them know there was a complaint filed against him and what the nature of it was.

Second, though, any client performing due diligence would have eventually come across notice of complaint against Charles. By pre-emptively notifying them, he would have removed the appearance of “trying to cover it up.” Even the appearance of unsavory behaviour could be seen as an ethical breach.

no need to volunteer info to other clients.

also it was pending allegations.

It is ethical, innocent of all accusations until proven guilty by your peers and the Board of Examiners.

Innocent until proved guilty!

Disagree with your conclusion. Not enough information. For example was engineer B trying to collect fees and client C filed the compliant? It was an allegation unless the engineer was found in the wrong he did not need to tell client B. Innocent until proven guilty.

Innocent until proven guilty. This is just an unproven allegation. at this time.

I agree that this is ethical per today’s standards but may have been poor judgement not to inform the client at an appropriate time.

I agree with the board, allegations do not need to be disclosed, but also agree it would have been prudent for Charles to let Client B know there might be something in the wind. I might have felt more strongly about the second part if the work hadn’t already been underway.

In this day of hyper-sensitivity and animosity by all sorts of groups — political, racial, economic strata, etc. — it seems the likelihood of smear allegations is higher than ever.

People, groups of friends, customers and clients all get along until someone, somewhere is found to belong to “the other”, or their ideas are not fully enlightened to to comply with the thought fashions of today, this week, or this year.

That’s when people get smeared and livelihoods are threatened. It happens all the time on social media, and I fear the barriers are eroding against more significant accusations.

You know, Bob the Engineer did a really good job for us. But I heard yesterday that Bob believes in X, doesn’t believe in Y, or voted for Z. You know, there was that part f the job that didn’t turn out well. Maybe it was Bob’s fault. The more I think (obsess) about it, it WAS Bob’s fault. I am now annoyed or angry. I think I’ll file a complaint. That’ll teach Bob not to believe in X, start believing Y, or not vote for Z.

Now, filing an ethics complaint may be a bridge too far for some. But posting a scathing online review (which may be equally false) often isn’t.

It sounds absurd, but the trend away from normal, rational adult behavior shows no signs of abating.

you’re confusing ethics with good judgment. It was not unethical to not notify Client B, as the board stated. But, it would have been good judgment for him to notify Client B, and explain the situation in a way that put himself in a better light (defended against the claim), rather than Client B finding out through other means. Also, as recommended by the board.