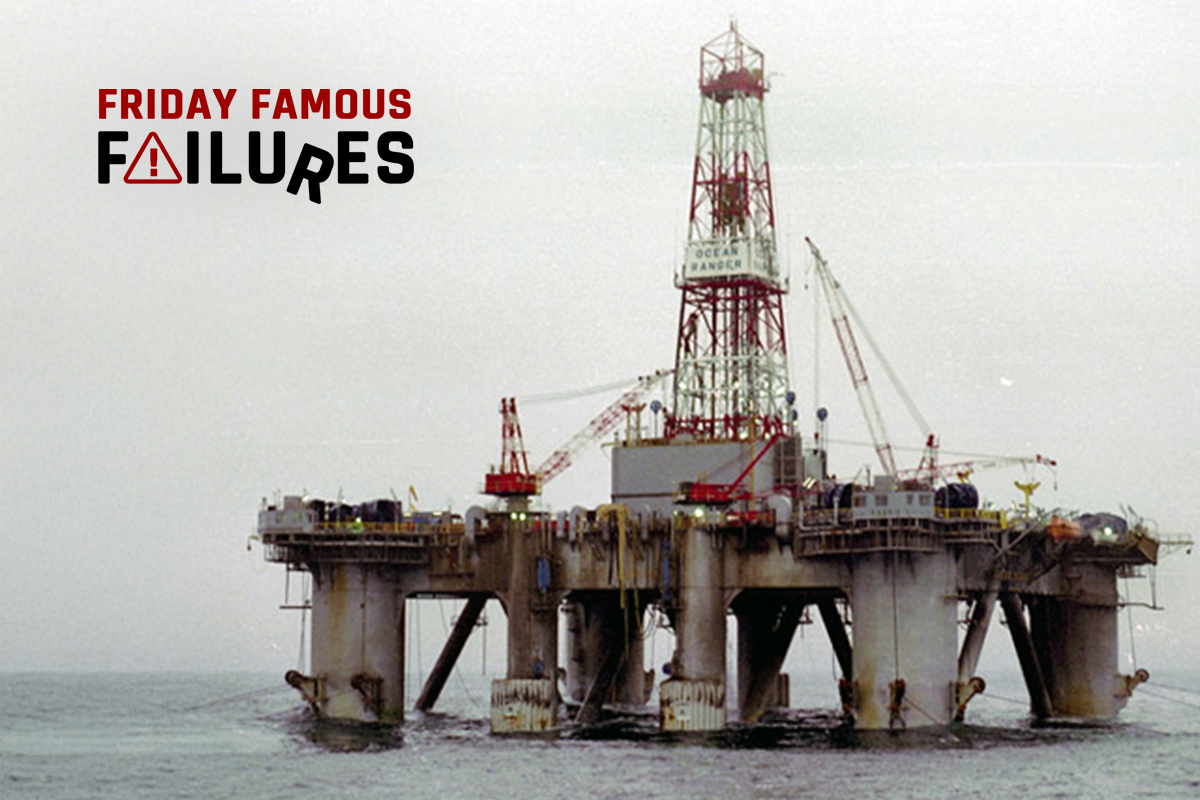

In 2008, the energy company BP received a permit to drill a subsurface oil well in the Gulf of Mexico called the Macondo well. For this project, BP chartered the 10-year-old rig Deepwater Horizon from its owner, Transocean. Halliburton was responsible for cementing work.

The Deepwater Horizon was celebrated as one of the safest drilling rigs in the world. In 2009, the Minerals Management Service identified the rig as a “model for safety.” The Associated Press noted that “its record was so exemplary, according to MMS officials, that the rig was never on inspectors’ informal ‘watch list’ for problem rigs.”

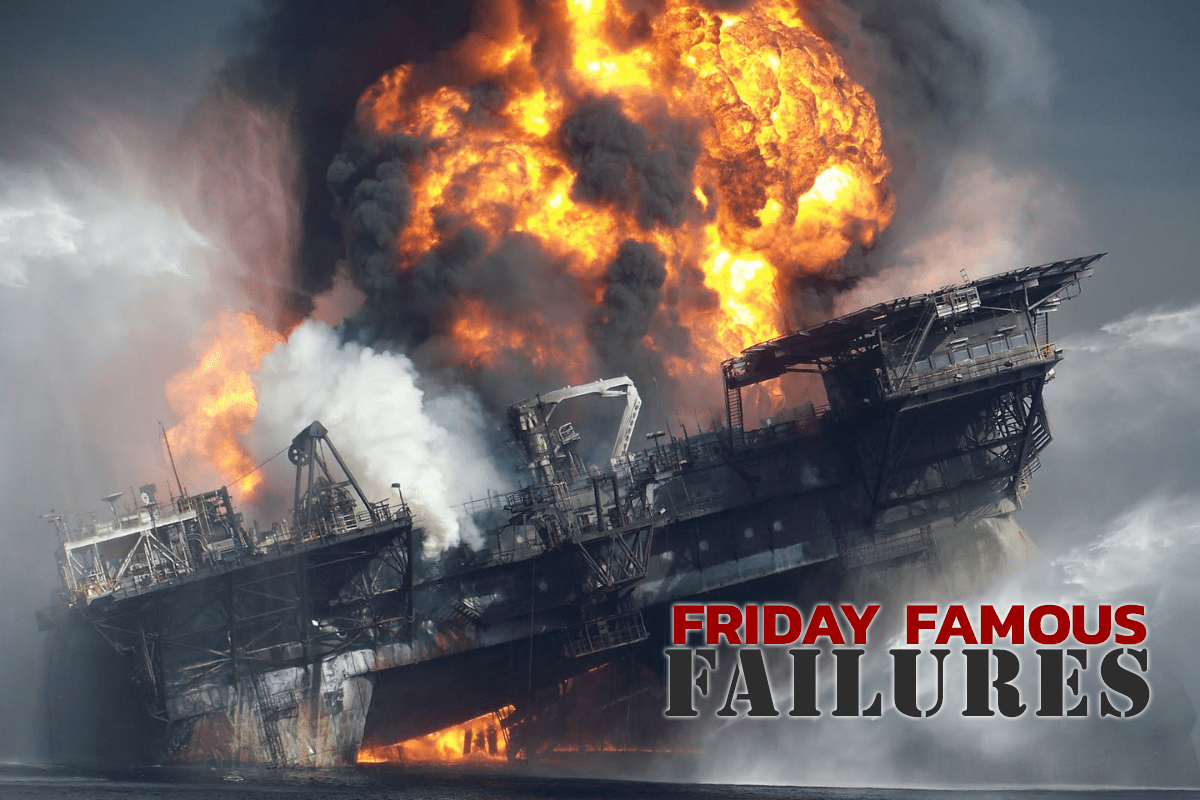

Yet despite this exemplary operational record, the Deepwater Horizon experienced a significant explosion due to gas blowback on April 20, 2010. The explosion killed 11 workers, and the resulting fire destroyed the rig in a day. The Macondo oil well began leaking oil after the explosion, creating one of the worst environmental disasters in US history. What went wrong?

What caused this disaster?

Lack of safety preparations / Poor safety culture. Deregulation permitted BP to file their request to drill the Macondo well without providing a blowout plan (detailed procedures for responding to an unintended sudden release of gas or oil from the newly drilled well). An internal survey of workers prior to the explosion indicated significant concerns “about poor equipment reliability, which they believed was a result of drilling priorities taking precedence over maintenance.” According to the survey, “many workers entered fake data to try to circumvent the system. As a result, the company’s perception of safety on the rig was distorted.”

Flawed blowout prevention system. The blowout preventer (BOP) installed at Macondo lacked either remote-control or acoustically activated triggers, which would activate it in case of emergency. The BOP did have a “dead man’s switch” that would activate and seal the well if platform communication was lost, but it is unknown if this was triggered. Also, Transocean had modified the BOP against their contractor’s warnings in a manner that increased the risk of failure.

Poor Drilling Practices. Subsequent investigation identified six factors within the drilling process that caused the blowout and explosion:

- Small diameter drilling hole. The hole diameter at the point of drilling was narrow, preventing enough of a gap between the drill and the walls of the hole to allow mud to circulate effectively. Also, the small diameter did not allow room for sufficient drill centralizers (devices to prevent the drill from contacting the side of the drill hole). Both of these effects violated “best practices” in the drilling industry.

- Backflow valves to prevent cement backflow did not close. Because of the small-diameter hole and lack of sufficient gap for mud circulation, an abnormally high amount of drilling pressure was required. Backflow valves were held open by pipes for injecting cement into the casing, then closed when the casing was full, and the cement lines were withdrawn. Because of the high drilling pressure, operators assumed the casing had filled with cement, and the lines were withdrawn, but that was not the case.

- Poor cementing of the casing. The narrow gap between drill and casing due to the small diameter hole prevented the casing from being flushed of contaminants prior to injecting the cement. This likely caused the cement to be poorly distributed, or structurally deficient, as well as contaminated with lower-density mud, or materially deficient. This also may have prevented the backflow valves from closing.

- Pressure readings wrongly interpreted. Operators had no detailed procedure for the “negative pressure test,” and drew incorrect conclusions from the high drilling pressure.

- Reservoir fluids not monitored. While displacing the drilling mud with seawater, operators did not monitor the mud outflow for reservoir fluids (i.e., gas), which would have indicated an impending blowout.

- BOP Failure due to off-center drill shaft. The insufficiently centralized drill shaft prevented the BOP from closing when gas reached the rig floor.

Effects of the disaster

There were signs of a potential blowout in the days prior to the explosion, particularly gas bubbling from the oil dome into the well itself. The rig was using heavy drilling mud, which helped keep the gas down during drilling operations, but on the day of the explosion, a BP official – aboard to celebrate seven years without a safety incident – directed the crew to replace the drilling mud with light seawater despite objections from the Chief Driller.

At 9:56 PM, the crew of the Deepwater Horizon noted that the lights flickered, and there were two strong vibrations. According to BP’s subsequent investigation, the explosion and fire occurred when a bubble of methane gas escaped the well (a textbook blowout) and traveled up the marine riser (the subsurface pipe to the surface), igniting when it was sucked into the air intakes of the diesel generators.

The explosion started a fire on the platform that was beyond the capacity of the Deepwater Horizon’s firefighting capacity. Rescue attempts began immediately, with 17 workers being airlifted to hospitals in nearby Mobile, AL for injury, and 98 workers being evacuated by lifeboat. Overall, 11 workers were never recovered and are presumed to have died in the explosion. The still-burning Deepwater Horizon sank a day later.

Although initial reports showed little to no oil leaking from the Macondo well, a few days later, a continuous oil spill was confirmed. Some 210 million gallons of oil leaked out of the well before it was plugged again, which is considered the worst environmental disaster in US history.

BP’s own investigation found that its employees and those of Transocean misinterpreted the pressure test and neglected potential blowout indications such as the riser pipe losing fluid. The report also acknowledged that BP did not listen to Halliburton’s recommendations for more centralizers, but concluded that this factor probably did not affect the cement. BP also said the crew should have redirected the flow of flammable gases. Transocean responded to the report by blaming the explosion on “BP’s fatally flawed well design.”

An investigation by the Oil Spill Commission issued conflicting opinions on whether BP ignored safety concerns. First, they concluded that BP had not sacrificed safety in order to make money, but then identified several poor management decisions regarding safety due to a “rush to complete work” on the well. At one point, their website enumerated eight risky decisions taken by BP prior to the explosion, but these were quickly removed. However, the Commission sharply criticized BP’s decision to ignore the computer simulation showing the need for additional centralizers and BP’s failure to re-check or re-run the simulation prior to drilling.

In 2014, a US District court ruled that BP was guilty of gross negligence and willful misconduct under the Clean Water Act while describing Transocean’s and Halliburton’s actions as merely negligent. The court apportioned 67% of the blame for the spill to BP, 30% to Transocean, and 3% to Halliburton. BP later reached an $18.7 billion settlement with the US government and the states of Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. BP was also required to clean up the environmental damage of the oil spill. BP’s total cost for the Deepwater Horizon accident was about $65 billion.

So, based on the information here, the probable proximate cause was the BP official’s direction to replace the heavy drilling mud with sea water. Anyone know what happened to that knucklehead? Likely got a promotion *sigh*.

Having spent 12 years in the O&G industry (many years ago now) there were many individuals of authority that would try to circumvent safety to increase profits. I had one drilling superintendent insist we re-use blow out preventer sealing rings. This is never recommended as they are a single use, deformed steel ring. I threw the old ones away so we didn’t have any to re-use thereby insuring the BOP’s were safe. Almost lost my toolpushing job over that; but, when I had to kill a well, and flare off the gas at least I had some level of confidence that everyone on the rig wasn’t destined to be a French fry. Those shortcuts are often mandated by those who won’t be in the danger zone if something happens. They also tend to have been lucky up to this point and don’t realize what a fickle mistress lady luck is. She needs to be taken out of the picture completely but at times is not. I have heard there were red flags on the DWH similar to this but no one had the moxie to take a stand and correct them.

God bless you Bradley. Doing the right thing, especially where safety in dangerous situations is concerned, is the only way to go.

This is an example of experienced men thinking they knew more than the science and what instruments and actual physical operating data showed them. BP hired these people and put them in a position to fail. Th4 fact that 11 people died is the true tragedy and I hope we will never forget this lesson. Don’t assume people put in positions of authority know what they are doing.

There’s a great book on this and previous actions of BP, Run to Failure. I was given a copy when I was hired by a different producer. I was in the Safety department.

The tragedies that result from, at least in part, from greed and hubris are just so preventable yet predictable that they are mind numbing. It is amazing how much pushback I received regarding safety through the years until we adopted a culture of ‘people first’. Although we have evolved as an industry, we must still remain vigilant.