This is the December 2019 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think? This series is comprised of case studies from NSPE archives, involving both real and hypothetical matters submitted by engineers, public officials and members of the public.

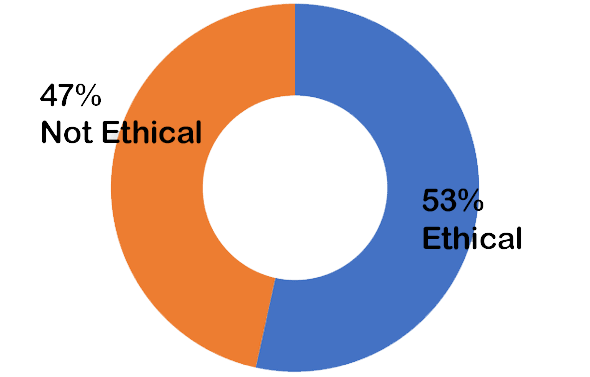

Your peers and the NSPE Board of Ethical Review have reviewed the facts of the case as shown below. And, here are the results.

A Review of the Facts

Smith is killed as a result of an alleged defective product. Smith’s widow, Mrs. Smith, is unable to afford the services of an expert to investigate the technical issues relating to the allegedly defective product. Mrs. Smith contacts Engineer Harry, a product design specialist who frequently provides forensic engineering and related services.

Following a long discussion, Mrs. Smith requests that if it is determined that a legal action should be brought against the manufacturer, that Harry act as Mrs. Smith’s agent to direct the legal action on her behalf. She requests that Harry advise her regarding the selection and retention of an attorney, and oversight of the attorney’s general approach to the case. Harry would not serve as an expert witness as part of the legal action. Since Mrs. Smith has limited resources, Harry, following considerable contemplation and thought, agrees to perform the services on a contingency fee basis, with Harry receiving a percentage of the settlement or award.

Was it ethical for Harry to agree to provide the services in question on a contingency fee basis?

Here is the result of our survey of your peers:

Applicable NSPE Code References:

Code Preamble: Engineering is an important and learned profession. As members of this profession, engineers are expected to exhibit the highest standards of honesty and integrity. Engineering has a direct and vital impact on the quality of life for all people. Accordingly, the services provided by engineers require honesty, impartiality, fairness, and equity, and must be dedicated to the protection of the public health, safety, and welfare. Engineers must perform under a standard of professional behavior that requires adherence to the highest principles of ethical conduct.

Code II.2: Engineers shall perform services only in the areas of their competence.

Code III.6a: Engineers shall not request, propose, or accept a commission on a contingent basis under circumstances in which their judgment may be compromised.

Discussion

The past 25 years has seen a dramatic evolution in the manner in which engineers are being called upon to provide professional services. This includes an array of innovative contracting techniques, partnerships and consortia with non-engineering public and private entities as well as other types of arrangements. This Board has from time to time examined the ethical responsibilities of engineers who are called upon to render services in non-traditional arrangements and relationships. As we have indicated in the past, engineers must be open to new and innovative techniques both in the technical and the professional sphere, and at the same time take appropriate and reasonable steps to ensure that their actions and conduct are consistent with the basic principles embodied in the Code of Ethics.

One of the areas that the Board has examined with great frequency involves those relationships where the relationship between the engineer and his client is based upon some contingent event or occurrence. Code III.6a. makes it clear that engineers should not request, propose or accept a professional commission on a contingent basis under circumstances in which their professional judgment may be compromised. The Board has interpreted this provision to indicate that a contingent relationship is not per se unethical but only those that may have the effect of compromising the professional judgment of the engineer.

The classic example of this would be the situation where the engineer proposes or is requested to perform a “feasibility study” for a client and the engineer’s fee is “contingent upon the result that the study will recommend that the project go forward.” It would be extremely difficult to disagree that such a contingency may have the effect of compromising the professional judgment of the engineer performing the feasibility study (for further discussion, see BER Case 65-4).

Other examples of cases considered by the Board involve contingencies where the engineer’s fee was based upon a savings to a client (BER Case 73-4). There the Board indicated that it was ethical for the engineer to be compensated on that basis, but also recognized that it is conceivable that the engineer could compromise his professional judgment under these facts by being overzealous in seeking means of savings to his client. Nevertheless, the Board concluded that “over-zealousness” can hardly produce a compromise of professional judgment, providing all other interests of the client, such as safety and reliability are protected.

More recently, in BER Case 91-2, the Board ruled that it was unethical for an engineer to agree to an arrangement whereby the engineer would review the work prepared by another engineer and identify errors/omissions contained in the documents in contemplation of a suit for breach of contract with the reviewing engineer’s fee dependent upon the ultimate court judgment or settlement. We noted that by finding no errors/omissions in the work, there would be no fee and that this appears to be just the very factors for which Code III.6.a. was intended to guard against.

Turning to this we believe that facts are distinguishable from those faced by the Board in BER Case 91-2. Unlike BER Case 91-2, it appears that Harry is being retained as an expert advisor and resource to Mrs. Smith in a variety of areas and is not being retained to provide direct technical assistance in support of Mrs. Smith’s claim. We believe the fact that Harry will not serve as an expert witness as part of the legal action is significant because it diminishes concern that as an expert witness Harry’s judgment may be compromised to support Mrs. Smith’s legal action.

While we believe that under the facts, Harry’s actions were not inconsistent with the Code of Ethics, we caution engineers who undertake the activities as those described. Also, we leave unexamined the issue of whether Harry or other engineers requested to provide such services possess the necessary training or expertise to serve in the role described as required by Code II.2a. Further, we would also note that some of the services Harry was asked and agreed to perform may indeed go beyond the practice of engineering. We advise that before agreeing to perform such services, engineers should be certain that they exercise exceptional caution that their opinions are not compromised.

We must again reemphasize our concern that any contingency fee basis arrangement must be carefully scrutinized by the engineer to make certain that the engineer’s judgment is not compromised. We surmise that many professional engineers within the forensic engineering community would disagree with the advisability of retaining engineers on a contingency fee basis.

The Ethical Review Board’s Conclusion

Assuming Harry made a decision that his judgment would not be compromised by the contingency fee issue, then it was ethical for Harry to agree to provide the services in question

BOARD OF ETHICAL REVIEW

John F. X. Browne, P.E.; William A. Cox, Jr., P.E.; Herbert G. Koogle, P.E.-L.S.; Paul E. Pritzker, P.E.; Harrison Streeter, P.E.; Otto A. Tennant, P.E.; Lindley Manning, P.E., Chairman

*Note-This opinion is based on data submitted to the Board of Ethical Review and does not necessarily represent all of the pertinent facts when applied to a specific case. This opinion is for educational purposes only and it should not be construed as expressing any opinion on the ethics of specific individuals. This opinion may be reprinted without further permission, provided that this statement is included before or after the text of the case.

Leave A Comment